. Introduction

The Zedmar culture (later: ZC) is one of the subneolithic cultures from the South-Eastern Baltic area. It was located (Fig. 1) in the eastern part of Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia and the northern part of the Masurian Lake District in Poland. First research was carried out by Prussian prehistorians at the beginning of the 20th century and later by Russian and Polish archaeologists. Despite a rather long history of research, many questions about the ZC phenomenon still remain.

Fig. 1

The ZC site location. 1 – Utinoe Boloto 1 and 2, 2 – Zedmar A and D, 3 – Dudka, 4 – Szczepanki 8 and 8A (www.dmaps.com/m/europa/baltique/baltique20.gil; modified).

The ZC, also known as the Serovo culture or the Zedmar type materials, is sometimes regarded as a local group of subneolithic Neman or Narva cultures (for more details see: Borowik-Dąbrowska and Kempisty, 1981; Guminski, 1999, 2001; Czerniak, 2007, 2008; Timofeev, 1998; Kukawka, 2010).

In that varied nomenclature at least one is certain: the ZC is part of the subneolithic1 world, established by late hunter-fisher-gatherer communities that were producing pottery. Still an important question is: how to describe the genesis of the Zedmar tradition? Should it be brought together with a wider cultural complex of East European roots or excluded from the mosaic of the Baltic Subneolithic? This is linked with the origin of pottery making in the area under study as well as the beginning of the ZC. In the literature there are a few theories which involve different subneolithic or neolithic cultures in that process (for example: Gumiński, 2011a). There are opposing opinions about the end of the ZC tradition. Some researchers suggest the ZC might have contributed to the development of one of the Late Neolithic cultures (Zalcman, 2010) or even might have lasted almost until the Early Bronze Age (Gumiński, 2001, 2005). Others see it more briefly (Kukawka, 2015). There is a lack of strong premises in archaeological assemblages to support or to prove the falsity of both hypotheses. The aim of the study is to create an absolute chronology of the ZC, after analysing radiocarbon data with Bayesian tools. The article is based on the author’s unpublished bachelor’s thesis and in a few cases related to absolute chronology of the South-East Baltic Neolithic, also presents results from master’s degree thesis.

. Methodological background

Since 1969 there have been many radiocarbon dates obtained from the ZC sites and 58 (Table 1) may be used in the further calculation with Bayesian analyses. They have been taken from seven sites, but, unfortunately, not all of them correspond to the ZC layers directly. As a result, for seven known and archaeologically excavated sites, only four have more than one radiocarbon date. What is more, only two of them (Dudka and Zedmar A) have sets of datings which can be used as a base in creating a sequence model. Unluckily, insufficient data makes it impossible to calculate them with a more precise tool (for example there are not known exact depths for each sample – for details see: Gumiński, 2001, 2005, 2014; Gumiński and Fiedorczuk, 1990; Timofeev et al., 1995, 1998). A similar situation is taking place in the case of Szczepanki sites 8 and 8A, where all 14C estimations (Gumiński, 2005; 2011b) were gathered from different trenches in order to build one chronological model. From Utinoe Boloto 1 and 2 came two radiocarbon dates (Timofeev, 1980). All the remaining radiocarbon dates were derived from Zedmar D site. They were obtained from five potsherds made in different technologies (two with a mineral admixture in clay mass and three with an organic). Two radiocarbon dates were estimated for each sherd. Both samples were prepared in a different way – INS and SOL fraction – (for a more detailed description see: Timofeev et al., 1995, 1998). Also from Zedmar D came the so-called “E group” selected from charcoal and wood fragments (Timofeev et al., 1995, 1998). The “L group”, which was also collected from Zedmar D, was excluded from further consideration, because it was linked with a younger settling episode (Timofeev et al., 1995, 1998).

Table 1

The radiocarbon dates obtained from the ZC sites.

| No. | Lab no. | Age BP | Material | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUDKA | |||||

| 1 | Gd-5575 | 7420 ± 80 | - | Late Mesolithic | Gumiński, 1998: 103 |

| 2 | Gd-5942 | 6910 ± 80 | - | Late Mesolithic | Gumiński, 1998: 103 |

| 3 | Poz-3913 | 6645 ± 30 | Human bone | Grave VI-17; with one “post Zedmar” potsherd | Gumiński, 2014: 125 |

| 4 | Gd-5944 | 6270 ± 70 | - | Late Mesolithic | Gumiński, 1998: 103 |

| 5 | Gd-5365 | 5540 ± 60 | - | Trench II | Gumiński and Fiedorczuk, 1990: 54 |

| 6 | Gd-2878 | 4960 ± 90 | - | Trench II | Gumiński and Fiedorczuk, 1990: 54 |

| 7 | Gd-4457 | 4880 ±120 | - | Leyer with the Late Neolithic, Trench III | Gumiński and Fiedorczuk, 1990: 69 |

| 8 | Gd-2593 | 4870 ± 110 | - | Trench II | Gumiński and Fiedorczuk, 1990: 54 |

| 9 | Gd-4871 | 4320 ±120 | - | Leyer with the Late Neolithic, Trench III | Gumiński, 1998: 103 |

| SZCZEPANKI 8 | |||||

| 10 | Poz-9384 | 5580 ± 40 | Charred food | A potsherd with organic and mineral admixture, from layer with “early Zedmar” materials and the Mesolithic | Gumiński, 2005: 57; 2011b: 90 |

| 11 | Sz8-BA* | 2900 ± 60 | - | The Bronze Age layer | Gumiński, 2011b: 90 |

| 12 | MKL-596 | 3980 ± 40 | - | The layer with the Late Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age materials | Gumiński, 2011b: 90 |

| SZCZEPANKI 8A | |||||

| 13 | Poz-48943 | 5360 ± 35 | The ornamented oar | The layer with “early Zedmar” materials and the Mesolithic | Gumiński, 2011b: 90 |

| UTINOE BOLOTO 1 | |||||

| 14 | Le-1237 | 4870 ± 230 | Charcoal | - | Timofeev, 1980: 14 |

| UTINOE BOLOTO 2 | |||||

| 15 | UB-2* | 4920 ± 200 | Bone fragment | Experimental date from LOIA lab | Timofeev, 1980: 45 |

| ZEDMAR A | |||||

| 16 | Le-1343 | 4260 ± 80 | Charcoal | Layer above teh upper horizon, which is linked with younger assembladges | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 17 | Le-1270 | 6000 ± 90 | Piece of wood | The pole dug into the ZC layer | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 18 | Le-1388 | 4920 ± 80 | Charcoal | The upper horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 19 | Le-1389 | 5100 ± 60 | Charcoal | The upper horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 20 | Bln-2165 | 5120 ± 50 | Charcoal | The upper horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 21 | Le-1319 | 4730 ±140 | Gyttja | The second layer | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 22 | Bln-2164 | 5100 ± 50 | Gyttja | The second layer | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 23 | Bln-2163 | 5300 ± 60 | Gyttja | Above the lower horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 24 | Le-1386 | 4870 ± 80 | Charcoal | The lower horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 25 | Le-1387 | 4900 ± 80 | Charcoal | The lower horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 26 | Le-3923 | 5130 ±100 | Charcoal | The lower horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 27 | Bln-2162 | 5280 ± 50 | Charcoal | The lower horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 28 | Le-1268 | 4955 ±110 | Charcoal | From the bottom of the The lower horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| 29 | Le-1269 | 5440 ± 90 | Charcoal | From the bottom of the The lower horizon | Timofeev, 1980: 9; Timofeev et al., 1998: 74 |

| ZEDMAR D | |||||

| 30 | Le-3626 | 4890 ±100 | Gyttja | The “E group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 23; 1998: 72-73 |

| 31 | Le-3921 | 5640 ± 300 | Antler tool | The “E group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 32 | Le-3924 | 5070 ±150 | Gyttja | The “E group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 33 | Le-3179 | 4880 ± 50 | Piece of wood | The “E group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 34 | Le-3173 | 4990 ± 45 | Piece of wood | The “E group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 35 | Le-3174 | 5090 ± 50 | Piece of wood | The “E group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 36 | Le-3181 | 5150 ±100 | Piece of wood | The “E group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 37 | Le-3176 | 5170 ±70 | Piece of wood | The “E group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 38 | Le-3925 | 3870 ± 290 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 39 | Le-3168 | 3890 ± 60 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 40 | Le-3171 | 4250 ± 40 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 41 | Le-3169 | 4300 ± 40 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 42 | Le-3992 | 4120 ±100 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 43 | Le-3177 | 4170 ±45 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 44 | Le-3170 | 4210 ±45 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 45 | Le-1181 | 4020 ± 80 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 46 | Ta-1173 | 4350 ± 80 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 47 | Le-848 | 4180 ± 50 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 48 | Le-1176 | 4240 ± 90 | Piece of wood | The “L group” | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 49 | Ua-2375 | 5180 ±100 | Charred food | An organic admixture, the potsherd 1, INS fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 50 | Ua-2376 | 5120 ±100 | Charred food | An organic admixture, the potsherd 1., SOL fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 51 | Ua-2377 | 5030 ±100 | Charred food | An organic admixture, the potsherd 2., INS fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 52 | Ua-2378 | 4950 ± 90 | Charred food | An organic admixture, the potsherd 2., SOL fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 53 | Ua-2379 | 4840 ±100 | Charred food | An organic admixture, the potsherd 3., INS fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 54 | Ua-2380 | 5100 ±100 | Charred food | An organic admixture, the potsherd 3., SOL fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 55 | Ua-2381 | 4810 ±100 | Charred food | A mineral admixture, the potsherd 4., INS fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 56 | Ua-2382 | 5230 ±100 | Charred food | A mineral admixture, the potsherd 4., SOL fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 57 | Ua-2383 | 5360 ±130 | Charred food | A mineral admixture, the potsherd 5., INS fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

| 58 | Ua-2384 | 5280 ± 80 | Charred food | A mineral admixture, the potsherd 5., SOL fraction | Timofeev et al., 1995: 25; 1998: 73 |

All gathered dates were calibrated and modelled with OxCal v. 4.2.4 (https://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk) with IntCal13 (Reimer et al., 2013). Parameters were written after Bronk Ramsey, 2008 and 2009. The entire set of 14C estimations was modelled with Sequence command (more complex models are impossible to apply due to the lack of stratigraphic data) or R_Combine parameter. The results are rounded to ten years and are given with 68.2% probability range in the paper unless stated differently. For comparison 95.4% confidence intervals are reported in tables. Agreement indices for each modelled radiocarbon dating are also applied into the tables.

All of the ZC sites excavated up to now have been peat bogs. Peat layers could accumulate in a quite turbulent way (see: Tobolski, 2000; Walanus and Goslar, 2009). This allows to raise a question if an application of any of stratigraphically based models into the analysis of the ZC sites is trustworthy. Especially when one is considering Zedmar A chronological model or stratigraphical schema from Szczepanki 8 and 8A.

There is one more issue which has to be noted. Putting aside some deposition controversy and old wood effect – which might be discussed in the case of all of the ZC sites – there are a few additional important problems with pottery dating. As long as it is not charred food or organic temper itself that is dated, there is a possibility of dating not the ‘target event’ (for description see: Richter et al., 2009: 711; a similar point of view Kukawka, 2010; Walanus and Goslar, 2009) but rather the natural component of clay (for discussion on that matter: Goslar et al., 2013; Kovaliuch and Skripkin, 2007; Kukawka, 2010). Maybe this is the reason why a few dates obtained from pottery fragments with mineral admixture seem to be older, although the authors of the study had tried to avoid such contamination (for description see: Timofeev et al., 1995, 1998). Even when sampling charred food for radiocarbon measurements one should also bear in mind that it might have come from cooking fish. This can result in a reservoir effect (compare: Lilie et al., 2009) which might be the case in the potsherd from Szczepanki 8. However, without a more detailed analysis of residue, it is only one of the possible explanations.

. Results and discussion

The Dudka site sequence of radiocarbon dates is a little incomplete, but even such an insufficient number of radiocarbon dates, when treated together, can give more precise information about the age of the studied events (for similar opinion see: Bayliss et al., 2007; Dee et al., 2013; Michczyński, 2011; Walanus and Goslar, 2009). Results are presented in Table 2. To narrow the intervals Mesolithic and Late Neolithic dates were built into the model. Thanks to this it was possible to estimate a more credible dating of the Middle/Late Neolithic culture settling episode. It may be seen especially in the case of the Gd-4457 sample (3900–3520 calBC separately calibrated; 3670–3370 calBC in a sequence – Fig. 2) which corresponds a little better with other dates of similar materials from neighbouring regions (ca. 3100 calBC). It still seems to be an outlier, but its agreement index is not so poor – 83.4 (when the overall for the model is 85.6).

Table 2

Results from Dudka sequence (OxCal v. 4.2.4).

From Dudka came the palynological profile, which was reported in 1995 (Nalepka). It seems that palynological and archaeological dating “is in agreement” (Nalepka, 1995: 64). However, radiocarbon date taken for the level with the early ZC (Gd-2593 sample) seems to be younger (Nalepka, 1995: 63–4). According to Nalepka (1995: 63), the disagreement may be caused by sampling material for radiocarbon dating not directly from the palynological profile. As it may be seen in Table 2 this sample corresponds quite well with the created model and there are no indicators that it may be an outlier. Perhaps this is another suggestion of how complex the process of layer accretion in Dudka was. Or how many data is missing in such simple model as presented in Fig. 2.

There is one more radiocarbon date from the Dudka site, taken from human bone, that may be linked with the ZC (Poz-3913 6645±30). However, the potsherd, which was found in the same grave, was described as the Late Neolithic and the dating result suggests Mesolithic chronology (Gumiński, 2014). This allowed archaeologist W. Gumiński (2014) to make an assumption of possible material mixing. Therefore, that sample was excluded from further consideration in this study.

Poz-9384 sample from Szczepanki 8, taken from charred food on a potsherd, after calibration gives 4490–4350 calBC with 95.4% confidence interval. Altogether with the other datings from Szczepanki 8 and Szczepanki 8A it may be treated as one stratigraphical schema (results in Table 3). It should be noted that the model was created after comparing stratigraphical and palinological analyses, which are quite compatible – Fig. 3 (also overall agreement for a model is quite high – 99.2), although the data were obtained from different trenches (Gumiński, 2011b).

Fig. 3

Sequence model for Szczepanki 8 and 8A after correlated stratigraphical data (OxCal v. 4.2.4).

Table 3

Results from Szczepanki sequence (OxCal v. 4.2.4).

Singular dates from Utinoe Boloto 1 and 2 have large uncertainties (Timofeev, 1980). The Le-1237 sample after calibration is dated 3950–3370 calBC in 68.2% probability range and 4240–3030 in 95.4% probability range. The UB-2 sample from Utinoe Boloto 2 is dated 3970–3380 in 68.2% confidence interval and 4240–3120 calBC in 95.3% confidence interval. Each sample covers ca. 600 years even with a 1σ interval, which makes the closer chronological analysis impossible.

Modelled age for the ZC layers from Zedmar A may be seen in Table 4. Overall agreement index for the model is 76.2. However, looking at all the dates obtained from Zedmar A (Table 1), it may be seen that a few dates do not correspond with given order. The Le-1270 sample at a guess estimate can be considered as an outlier. Moreover, a few failed calculations due to low agreement indices and were excluded from the final sequence (Fig. 4) – Le-1269, Le-1268, Le-3923, Le-1387, Le-1396, Bln-2163, Le-1319. According to Michczyński (2011: 174–175), it is possible in a complex model to accept dates with agreement indices under 60%, but in the case presented above, the difference seems to be too high (much under 50%). It may be caused by disturbed material accretion on peat-bog sites and/or dating older wood fragments.

Table 4

Results from Zedmar A sequence (OxCal v. 4.2.4).

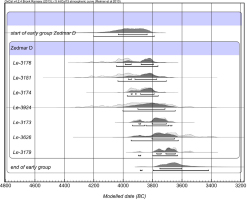

The “E group” of radiocarbon datings from Zedmar D was modelled with Boundary and Phase command (results in Table 5). Its agreement index is 94.9 after the Le-3921 sample has been excluded (it had a very poor agreement – 37.2).

Table 5

Results from modelling so-called “E-group” from Zedmar D (OxCal v. 4.2.4).

Combined intervals were created for Zedmar D ceramics. Results were derived from every two dates of each pottery sherd (Table 6), from both fractions (Table 7) and from both tempers (Table 8). It is quite troublesome to determine which (if any) of those results are more convenient. An archaeologist would say that ranges which were received for combined sherds with the same temper, while a radiocarbon lab worker would probably suggest a separate treatment of every sherd and/or dates from two fractions. There is a possibility that all the radiocarbon dates for Zedmar D collected from pottery sherds should not be treated in the way mentioned above (combining all of the dates from the pottery together) - for example, because of their lack of homogeneity (they could be deposited in more than one settling episode, so they do not represent the same event).

Table 6

Combined 14C dates for each potsherd from Zedmar D (OxCal v. 4.2.4).

Table 7

Combined 14C dates for each fraction from Zedmar D potsherds (OxCal v. 4.2.4).

Table 8

Combined 14C dates for organic and mineral temper from Zedmar D (OxCal v. 4.2.4). Result from mineral temper after excluding the Ua-2381 sample.

The variations in samples’ ages might also be caused by different laboratory preparation of samples – this is especially evident when taking into consideration INS and SOL fraction from the fourth potsherd. It is incorrect to combine both dates obtained from this piece of ceramic, because of failing a X2 test (Table 6, Fig. 6).

Due to the lack of certainty over the homogeneity of the analysed material, there are two versions of sequence model with Boundary and Phase parameters (Tables 9 and 10). When comparing those results it may be seen that pottery with a mineral temper has an older chronology than that with an organic temper. Then the Ua-2381 sample is an outlier (Table 9) – as in the case of combining all 14C dates for a mineral admixture. Another possibility is that the INS fraction is a better (but still not perfect) way to prepare samples with a mineral temper (at least in this case). As like this, the Ua-2381 sample is only one correct date for ceramic vessels with a non-organic admixture and corresponds quite well with the other samples taken from the second technological group.

Table 9

Results from modelling combined 14C dates for each potsherd (OxCal v. 4.2.4). The fourth potsherd was excluded from calculations.

Table 10

Results from modelling combined 14C dates for each potsherd (OxCal v. 4.2.4). The fifth potsherd and the older sample (Ua-2382) from the fourth sherd were excluded from calculations.

After comparing those results with each other and with the other dates from Zedmar D (Fig. 5) it is possible to exclude at least a few samples obtained from potsherds (mainly with mineral admixture). It seems that it would be more reasonable to date the ceramics from Zedmar D in-between 4060/3790–3780/3480 calBC, basing on the model from combined radiocarbon dates obtained from potsherds with organic temper and the Ua-2381 in 68.2% confidence interval. Again – it is possible that 14C estimations for Zedmar D (taken from pottery and the so-called “E group”) came from various settlement phases. But for what is known for now, all of the materials may be treated as deposited in one event – as long as there is no clear indication how to separate data.

It is worth mentioning that before World War II there were also palinological analyses conducted by H. Gross on two sites of the ZC (Gaerte, 1929; Okulicz, 1973). Unfortunately, some documentation and many artefacts have gone missing. From the published data it is known that the Zedmar site and the Moczyska site (later recognized as Dudka – Gumiński and Fiedorczuk, 1990) were settled at a similar time (Okulicz, 1973) – but further excavations and material analyses failed to find a correlation with those results (Borowik-Dąbrowska and Kempisty, 1981). Still, they may be used as a premise for synchronic or shorter time settling of the ZC sites.

Comparing results of the modelled age of the older layer from Szczepanki with the younger one and with the results estimated for Zedmar A it seems that the interval finishing older phase (4310–3840 calBC) is more trustworthy when one determines Szczepenki chronology.

What can be said about the ZC absolute chronology is that it may be estimated between 4240 and 3480 calBC. The beginning of it was taken from the modelled age of the older layer from Zedmar A (4290/4090–4220/4060 calBC with 4240–4100 calBC for Bln-2162). The finishing range was taken after the sample from ending boundary for the second pottery model (3780–3480 calBC) after considering the end of the ZC phase onto Dudka site (3760–3530 calBC). Although there are not many issues certain in archaeology and radiocarbon dates modelling, the study presented above is still one of the most complex analyses of the ZC absolute chronology. There are some premises not to date the ZC material earlier than 4100 calBC, as combined age from pottery from Zedmar D or “Zedmar” layer from Dudka site. But with a possibly younger date than the layer from which the Gd-2593 sample (discussed above) was taken and due to a few parallel ways of interpreting radiocarbon datings from Zedmar D it is difficult to sustain.

. Conclusions

There is some data which could clear the absolute chronology of the ZC up and some resolutions may be suggested. First, in the light of the results presented above, it is possible that the ZC could have lasted more briefly that it is usually stated. Nonetheless, due to the lack of dating materials and other methods of absolute age estimation, the long chronology of studied materials cannot be validated yet. There is also an option that some assemblages were misread or some stratigraphical records were incorrectly interpreted, in which case archaeologists should not consider the Zedmar materials as a separate archaeological culture, but rather as a local group of a larger structure. Then the question would be of which one.

As mentioned in the introduction, the ZC materials are characterised by a significant degree of syncretism and incorporating them into, say, Narva or Neman cultures is a matter of discussion among archaeologist from many countries. It can be said that it could be recognised as a distinctive feature of the ZC. For now, the first stated solution (the short chronology) seems to be more credible. With such an approach the ZC duration is closing between 4240–3480 calBC. Maybe a merged study with a more detailed look into archaeological assemblages of synchronic cultures could be more productive. However, subneolithic materials from the neighbouring area are poorly dated, so referring to them is even more difficult.