. Introduction

The Danube terrace staircases in Hungary developed between the uplifting areas of the Transdanubian Range and the North Hungarian Mountains and the subsiding Little Plain and Great Hungarian Plain. Different uplift and subside rates and periodic climate changes affected the formation of the terraces during the Late Pliocene and Pleistocene. The chronology and correlation of the Danube terrace system in Hungary are based on the geomorphic position of the terrace segments, rare palaeontological findings (e.g. Pécsi, 1959; Kretzoi and Pécsi, 1982; Virág and Gasparik, 2012), U/Th ages (e.g. Kele 2009; Sierralta et al. 2010), magnetostratigraphy (e.g. Lantos, 2004) and, from recently, cosmogenic nuclide (3He, 10Be, 26Al) dating and optically stimulated luminescence dating (e.g. Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger et al., 2005b, 2016, 2018). The age of the Pleistocene formations was frequently expressed according to the Alpine chronostratigraphic terminology. Besides this, the recently used Central European chronostratigraphy and/or the marine isotope stages (MIS) are also indicated in this study, according to the Stratigraphic Table of Germany (STD 2016).

Sedimentological and petrological data also support the correlation of the terraces, e.g. roundness of gravels (Pécsiné Donáth 1958; Burján 2000) and heavy minerals (Burján 2003). In the NE part of the Transdanubian Range, at the Gerecse Hills, a new terrace system was established by Csillag et al. (2018) and Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger et al. (2018) with new chronology on the basis of the novel age data together with the geomorphological, geological and palaeontological observations. But numerical age data and palaeontological findings are very scarce in the Pest Plain. Therefore, the first aim of this study was to date sediments on the area of the Danube terraces on the Pest Plain. The second aim was to compare the optically stimulated luminescence ages of coarse-grain quartz and feldspar of the same sediments. Hence, sandy sediments were collected from five outcrops and dated by SAR-OSL and post-IR IRSL290 methods.

. Geology and Geomorphology of the Study Area

The study area is the Pest Plain (Figs. 1 and 2). It is situated near River Danube in the surroundings of Budapest, between hilly areas (Gödöllő Hills, Buda Mountains and Visegrád Mountains). The basement of this plain lies about 600–1500 m in depth, and consists of Upper Triassic and Lower Jurassic dolomite and limestone, which was formed from the sediments of the Tethys sea (Haas et al., 2010). These Mesozoic carbonate rocks are covered by Eocene limestone and marl. Above them, hundreds meter thick sediments of the Paratethys sea were deposited, mainly Oligocene and Miocene clay, sandstone, sand and limestone, with intercalations of thin volcanic tuff layers (Jámbor et al., 1966b). In the Late Miocene, after the folding and uplifting of the Carpathians due to the subduction of the European foreland (Horváth, 1993), the area was part of the brackish–freshwater Lake Pannon, which as a remnant of the Paratethys sea occupied the Pannonian Basin. The lake was filled with the sediments of fluvial-dominated delta systems prograding from NW and NE directions (e.g. Magyar et al., 2013). The deltas gradually transformed into alluvial plains and the Hungarian part of the lake was filled up by the Pliocene (e.g. Gábris and Nádor, 2007). From the Late Miocene, certain areas were subsided and others were uplifted due to the NW–SE and N–S compression stress field (e.g. Horváth and Cloetingh, 1996; Fodor et al., 2005). The course of the rivers was influenced largely by the neotectonic deformations. In the Late Pliocene, the Palaeo-Danube probably flowed in the western part of Transdanubia, far from the recent channel of the Danube (Szádeczky-Kardoss, 1938, 1941; Gábris and Nádor, 2007). There is no consensus on the date, when the Palaeo-Danube changed its flow direction and cut the Miocene andesites of the Visegrád and Börzsöny Mountains at the Visegrád Gorge (Fig. 2). Urbancsek (1960) and Borsy (1989) supposed that it happened during the Late Pliocene; Mike (1991) and Neppel et al. (1999) presumed the Günz– Mindel (Cromer–Elster) interglacial. However, based on the palaeontological and paleomagnetic data (Kretzoi and Pécsi, 1982; Lathman and Schwarcz, 1990) the maximum age of this incision is Early Pleistocene (2.4–1.4 Ma). But, assuredly, after the Palaeo-Danube cut the Visegrád Gorge, it flowed in the SE direction for a long time, and not in its recent N–S course, collecting the water and sediments of many palaeo rivers (Gábris 1998, 2002). Then, due to neotectonic movements, the channel of the Palaeo-Danube gradually shifted from east to west, and the river reached its recent N–S flow direction during the Riss–Würm interglacial (Urbancsek 1960) which corresponds to MIS 5e or Eemian interglacial period, or only in the Holocene (Somogyi, 1961; Rónai, 1985).

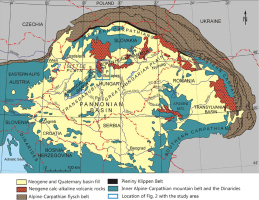

Fig 1

Location of the study area and geological surroundings after Horváth and Cloething (1996). P: Pest Plain, G: Gerecse Hills, S: Süttő, K: Katymár, Pa:Paks.

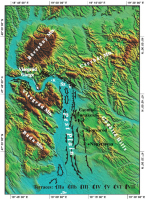

Fig 2

Pest Plain and the surrounding areas with the locations of the sampling sites and the terraces of the Danube. Terraces are based on Pécsi et al. (2000), Sz: Szentendre Island, K: Kisoroszi, V: Vác, Dv: Dunavarsány.

On the uplifting areas northwest from the Pest Plain, six or maximum eight terraces were developed at the Danube band, according to Pécsi (1959) and Kretzoi & Pécsi (1982), and in the Gerecse Hills, eleven terraces were recently identified by Csillag et al. (2018). On the Pest Plain, between the uplifting hilly areas, five Pleistocene terraces were formed by the Danube, based on the traditional terrace classification (Fig. 3; Pécsi, 1958, 1959).

The valley of the Danube is located at about 122 m asl. in the northern part of the Pest Plain and at 97 m asl. in the southern part of it, at Budapest. Towards south, the terraces lie gradually at lower altitude in the direction of the sinking Great Hungarian Plain, where the river built a huge alluvial fan.

First of all, the position and characteristics of the terraces on the Pest Plain were studied in detail by Pécsi (1958, 1959, 1996). According to him, terraces V and IV occur only in the south-eastern part of the Pest Plain. Terrace V is built up from gravel with about 14 m thickness, while terrace IV consists of a 1–2 m thick gravel layer with 3–4 m sand on it. The sediments show signs of cryoturbation and solifluction. The gravels are mainly from quartz and quartzite, and partly from andesite of the Visegrád Mountains, and limestone from the Gerecse Hills of the Transdanubian Range. In some places, these sediments are covered by travertine. Based on fossils of Mastodon borsoni (Mammut borsoni), it was thought that terrace V was developed during the Günz (~Cromer), but the last occurrence of the Mammut borsoni is much older, 2.0–2.4 Ma according to Virág (2013). Mastodon (Dibunodon) arvernensis, Mammuth americanus praetypicus and Dicerorhinus megarhinus remnants were also found in this gravel body (Jámbor et al. 1966a) and bones of Late-Pliocene Stephanorhinus megarhinus were described at Rákos, in the eastern part of Budapest (Kretzoi 1981). The cosmogenic 3He exposure minimum age of terrace V is 800 ka (Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger et al. 2005a). Remnants of Elephas trogontherii (Mammuthus trogontherii) in terrace IV were counted to the Mindel glaciation (Pécsi, 1959) which correspond to Elster glaciation or MIS 10, but the age of these fossils is from 0.8–0.7 Ma to ~0.2 Ma (Virág, 2013). The incision of this terrace happened between 410 and 390 ka ago (in MIS 11) due to a sudden warming episode, according to the termination model (Gábris, 2006, 2013).

Terrace III runs in a narrow range between the older and younger terraces, 27–30 m above the recent level of the Danube. Its age is Riss (Saale, MIS 8 – MIS 6) according to Pécsi (1959), or minimum 170 ka (Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger et al., 2005a). This terrace can be divided into IIIb and IIIa terraces, and their staircases were formed by the incision of the Danube 330–315 ka and 220–190 ka ago, respectively (Gábris, 2006, 2013). In some places, the fluvial sediments of this terrace are covered by 190–175 ka old travertine (Scheuer & Schweitzer, 1988).

Terrace II also consists of two levels. Terrace IIb can be followed through the Pest Plain parallel to the Danube. The gravel layer of this terrace is about 7–10 m thick and lies at about 15–20 m above the current level of the Danube. The quartz and quartzite gravels of the younger terrace sediments are more rounded (Pécsiné Donáth 1958). Elephas primigenius (Mammuthus primigenius) bones at Vác and Budapest indicate Late Riss (Late Saale) and Early Würm (Early Weichselian) (Pécsi, 1959). According to Gábris (2006, 2013), the stair of terrace IIb was formed by incision between 130 and 123 ka. 2–3 m thick fluvial sand and several meters thick aeolian sand cover the gravel. They show solifluction phenomena at some places. Loess with 1–2 palaeosoil layers also can be found on this terrace.

Terrace IIa is 8–10 m above the current level of the Danube and developed at the end of the Pleistocene, during the Late Würm (Late Weichselian) period. The stair of this terrace started to form after the Last Glacial Maximum, or about 19–17 ka ago (Gábris, 2006, 2013). Usually, this terrace is covered by aeolian sand. 18±2.5 ka old fluvial sediments and 16–0.6 ka old aeolian sands with paleosoils between them were dated by luminescence (TL, IRSL) and radiocarbon methods at Kisoroszi and Dunavarsány (Fig. 2, Ujházi et al., 2003; Gábris, 2003).

Terrace I is represented by overbank sediments at 5–7 m above the current level of the Danube. It is built up of fluvial sand and silt, which were deposited during the Early Holocene. The lowest level along the river also consists of overbank deposits, but in the lower position, 0–5 m above the level of Danube (Pécsi, 1996). In the abandoned arms of the Danube swampy environments developed.

The terrace levels are not in their original position because the neotectonic movements replaced them into gradually lower positions in the direction of the sinking Great Hungarian Plain (Fig. 3).

The surface of the terraces was altered during the forthcoming interglacial and glacial periods. They were covered mainly by aeolian sediments (loess or aeolian sand), and in some places by fluvial sediments and travertine. Under the modern soil layer mostly Weichselian sediments can be found. During the cold and dry periods in the Weichselian open coniferous taiga forests and steppe mosaics were characteristic for the plain areas of Hungary (Járainé Komlódi, 2000). This climate and the scarce vegetation favoured the sand and silt movement by strong winds, first of all, during the Weichselian High Glacial in MIS 3, and the Last Glacial Maximum in MIS 2. Loess formation in MIS 3 and MIS 2 was documented in many places of Hungary (e.g. Sümegi and Krolopp, 1995; Novothny et al., 2010b, 2011; 2020; Gábris et al., 2012; Thiel et al., 2014). Aeolian sand bodies, which were dated on the terraces and alluvial fans deposited mainly in MIS 2 according to the above-mentioned references and also e.g. Novothny et al. (2010a), and in MIS 3 as well (Sümegi et al., 2019). During milder or warmer phases, forest-steppe and pine-birch forests mixed with deciduous trees expanded (Járainé Komlódi, 2000), and mainly chernozem or chernozem-like and forest paleosoils developed on the loess and blown sand (e.g. Gábris et al., 2012).

. Samples and Study Methods

Samples

For optically stimulated luminescence dating, the samples were collected by opaque PVC tubes from five outcrops on different terraces of the Danube (Table 1; Fig. 2). For environmental dose determination, about 1 kg bulk samples were collected from the near surroundings of each OSL samples. In addition, some sediment was taken into tight closed containers (plastic boxes) for water content measurements.

Table 1

Location and main characteristics of the samples.

Two fluvial samples, medium-grained sand with gravel are from the Nagytarcsa gravel mine which represents terrace V according to the geomorphological map of Pécsi et al. (2000). The samples are from a depth of 7.0 and 7.9 m under the current surface (Fig. 4E). The 10–12 m thick terrace sediments consist of gravel and gravelly sand layers with planar and cross lamination. The average size of the gravels is 2–6 cm. Quartzite and weathered volcanic rock gravels are abundant, while chert gravels are rare. The volcanic rock gravels originated from the Visegrád Montains (Fig. 2).

Fig 4

Position of the samples in the sampling sites. A: Mogyoród gravel mine (aeolian sand), B: Dunakeszi sand mine (fluvial and aeolian sand), C-D: Fót sand mine (slope, reworked fluvial sand), E: Nagytarcsa gravel mine (fluvial sand), F: Csomád sand mine East wall (aeolian sand), G-H: Csomád sand mine West wall (fluvial sand).

Aeolian fine sand layers at 1.3 and 2.4 m depth were sampled from a dune on terrace V in the Mogyoród gravel mine (Fig. 4A). The ~3.5 m high dune is built up from fine and medium grained sand layers with cross stratification. Under the dune the gravel layer of the terrace is only 0.5–0.6 m thick, and contains mainly quartzite, weathered volcanic rock and subordinately gneiss gravels.

Four samples were collected for dating from the Csomád sand mine on terrace level III (Fig. 4F-H). Two aeolian silty fine sand samples are from the East wall of the mine at depth 1.6 and 3.2 m. The other two samples are fluvial fine-medium grained sands from the West wall of the mine from 2.4 and 4.4 m depth, which represent the sediments of a small stream. The sand bodies are cross-laminated and their thickness in the outcrops is about 2 and 3 m, respectively.

Reworked fluvial fine-medium sands of slope sediments were sampled for dating on terrace III in the Fót sand mine, from a depth of 1.8 and 3.5 m (Fig. 4C and D). The total thickness of these sediments is about 3 m and they show cross and planar lamination.

On terrace IIb, fluvial and aeolian fine and medium-grained sand samples were studied between depths of 1.9 and 7.4 m in the Dunakeszi sand mine (Fig. 4B). Here the minimum 2.5 m thick fluvial sand of a stream shows mainly planar bedding and contains thin gravel layers and lenses. Quartz, quartzite and relatively fresh volcanic rocks are frequent with a size of 0.3–1.0 cm. The thickness of the aeolian sand is about 2–3 m. It is cross-laminated and contains many rhizoconcretions.

Sample preparation

Sample preparation for optically stimulated luminescence dating was carried out under subdued red light conditions. Quartz and K-feldspar grains were extracted from the 0.1–0.2 mm grain size fraction of the sediments using 20% H2O2 to remove the organic material, 10% HCl to dissolve carbonates, 0.01N Na2C2O4 for desaggregation and cleaning of the surface from the grains, and aqueous solution of sodium polytungstate (3Na2WO4 · 9WO3 · H2O, SPT) with 2.67 and 2.58 g/cm3 for density separation. After these treatments, the quartz separates were etched by 40% HF for 90 min, or samples Dk1-5 for 60 min, to eliminate the outer 10–15 μm layer from the surface of the grains which was affected by the environmental alpha radiation. Then, 10% HCl was used to dissolve fluorides which were precipitated during etching. Finally, the 0.10–0.16 mm quartz and feldspar grains were separated by dry sieving.

The grains were mounted in monolayer on stainless-steel discs using silicone oil spray. The size of the aliquots was 2 mm diameter (small aliquot) in the case of feldspar, and 5 mm diameter (medium aliquots) in the case of quartz due to the relatively weak OSL signal of the quartz of the studied samples.

Before gamma spectrometry measurements, the bulk samples were dried, and the >1 mm grains were crashed. The sediments were filled into Marinelli beakers and they were stored in the closed containers for more than 28 days to reach equilibrium between radon and its daughter isotopes.

Optically stimulated luminescence measurements

Luminescence measurements were made by Risø TL/OSL DA- 15C/D and DA-20 readers in 2013 and 2019. Blue light stimulated luminescence of quartz was detected through a Hoya-340 filter, while infrared light stimulated luminescence of feldspar through a Schott BG-39 and Coring 7-59 filter combination. A calibrated 90Sr/90Y beta source was used for irradiation with a dose rate of about 0.092 Gy/s in 2013, and 0.081 Gy/s in 2019.

Single-Aliquot Regenerative-dose (SAR) OSL protocol (Wintley and Murray, 2006) was used on quartz, and post-IR IRSL (290 ºC) on feldspar (Thiel et al., 2011, 2012). In the case of quartz, according to the results of the preheat plateau test, 240°C preheat temperature was applied during the OSL measurements of the samples from the Dunakeszi sand mine, while 260°C preheat temperature for the other samples, and the cut heat was 200°C. The thermal transfer test indicated that the thermal transfer is negligible using these preheat temperatures. The purity of the quartz separates was checked by the measurement of OSL depletion due to infrared stimulation on every measured aliquot in an additional last cycle of the SAR-OSL protocol. During the evaluation of the OSL signals, early-background subtraction method (Cunningham and Wallinga, 2010) was applied, i.e., the 0.8–1.6 s integral of the OSL decay curve was subtracted from the initial 0.8 s integral signal to avoid a contribution from medium and slow components. The dose-response curves were fitted by single saturation exponential function. The dose recovery test was performed on 3 aliquots of each sample which display natural luminescence signals below saturation level.

K-feldspar was measured by post-IR IRSL290 protocol with 320°C preheat before IR stimulation at 50°C for 200 s, then at 290°C for 200 s, and illumination at 325°C for 100 s in the last step of each cycle according to Thiel et al. (2011; 2012). The test doses were relatively small, about 15% of the natural equivalent doses. From the initial 2 s of the post-IR IRSL290 signal the last 40 s was subtracted, similarly to Thiel et al. (2012). A single saturation exponential function was used for fitting dose-response curves.

Residual doses and dose recovery ratios of the feldspar separates were measured after 12 h bleaching on changeable (sometimes cloudy) sunlight in winter except for the saturated samples. The bleachability of the post-IR IRSL290 signal of four feldspar separates was also observed by bleaching them on bright sunlight in summer (in August) for 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 26 and 30 h before the residual dose determination. The fading test according to Auclair et al. (2003) was performed with 26.3 h maximum delay time on one aliquot of each K-feldspar separate, which natural luminescence signal lies below saturation level. The given dose was close to the natural equivalent dose of the samples.

Dose rate determination

Calculation of the environmental dose rates is based on laboratory high-resolution gamma spectrometry measurements. They were made by Canberra GC3020 on 0.8–1.0 kg bulk samples, and provide U, Th and K concentrations. Dose rate conversion factors given by Adamiec and Aitken (1998), attenuation factors of Mejdahl (1979) were applied. 12.5±0.5% K concentration (Huntley and Baril, 1997) and 0.15±0.05 a-value (Balescu and Lamothe, 1994) were used during the calculation of the internal dose rate of feldspar. The cosmic dose rate was determined according to Prescott and Stephan (1982) and Prescott and Hutton (1994).

The water content of the sediments was determined at the time of sampling and after saturation by water in a laboratory. The results helped to estimate the water content of the dated sediments during the time period of burial. It was taken 5±1% for the dune sands, and 11±2%, 14±3% or 18±3% for the fluvial sediments (Table 2).

Table 2

Dose rate determination.

Sample preparation, luminescence, gamma spectrometry, and water content measurements were carried out at the Mining and Geological Survey of Hungary (MBFSZ, former Geological and Geophysical Institute of Hungary).

. Results and Discussion

The results of dose rate determination are in Table 2. The optically stimulated luminescence test measurements indicated that quartz and K-feldspar fractions of the samples are good for precise age dating, except two samples with saturated quartz OSL and feldspar post-IR IRSL290 signals.

OSL measurements on quartz

Dose recovery ratios of quartz are satisfactory, 1.05±0.02 on average (n=39, Table 3). Some aliquots were rejected due to an inadequate result of IR test (feldspar or mica contamination), or high recuperation, or bad recycling ratio. Recuperation of the accepted aliquots is low, 1.02±1.09 on average (n=403). Quartz OSL dating is based on equivalent doses of 23–56 aliquots per sample (Table 4). The De values of the studied quartz fractions have a relative error in a range of 3.9–9.6%, precision (reciprocal standard error) ~10–25, and relatively high dispersion. These characteristics were visualised in the bivariate plots (radial plots based on Galbraith, 1988; Galbraith and Roberts, 2012) of abanico plots (Dietze et al., 2016). The representative examples are shown in Fig. 5A and C. On the right side of the abanico plots the histograms refer to more or less symmetric De distributions, and the kernel density estimate curves indicate that the De-s of each sample belongs to one population.

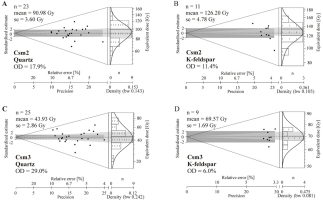

Fig 5

Representative examples for visualisation of the characteristics and distributions of the equivalent doses in abanico plots. A and C: De-s were measured by SAR-OSL protocol on medium (5 mm) aliquots of quartz, B and D: De-s were determined with post-IR IRSL290 protocol on small (2 mm) aliquots of K-feldspar. (Abanico plot: http://rlum.geographie.uni-koeln.de:9418/packages/RLumShiny/inst/shiny/abanico/).

Table 3

Dose recovery ratios.

In the case of sample Dk4 more than fifty aliquots were measured to get more symmetric distribution. Except for two samples, the overdispersion of the De-s changes between 12 and 22% (Table 4; Fig. 5A), indicating that the quartz of these sediments was probably well bleached at the time of deposition according to Olley (2004). Therefore, their age was calculated by the mean De values, which are almost identical to the central De-s, using the central age model of Galbraith et al. (1999). But, the equivalent doses of the quartz from fluvial samples Csm3 (Fig. 5C) and Dk3 show 29% and 30% overdispersion values. The large spread of De-s (9–32 Gy and 20–80 Gy respectively) can be caused by beta dose heterogeneity, partial or heterogeneous bleaching, and post-depositional disturbance (Olley, 2004). There is no sign of post-depositional disturbance in the studied sections. Probably, the quartz of these samples was not partially bleached before deposition because their kernel density plots in the abanico plots show only one De population and their mean and central natural equivalent doses are also very close to each other (central value is 44±3 Gy for Csm3, and 19±1 Gy for Dk3). Therefore, despite the larger overdispersion the quartz age of these two samples was calculated by the mean De-s. The quartz OSL ages of the dated sediments range between 14±1 and 43±4 ka (Table 4).

Table 4

Dating result of quartz and K-feldspar

[i] n: number of aliquots; OD: overdispersion; *: 2xD0; **: residual dose in % of the measured natural dose;

w: residual dose after 12 h exposure to changeable sunshine in winter;

s: residual dose after 4 h exposure to bright sunlight in summer;

a: assumable residual based on the correlation with quartz ages;

no subtr.: feldspar age without subtraction of residual dose;

w. subtr.: feldspar age with subtraction of residual dose after 12 h exposure to changeable sunshine in winter;

s. subtr: feldspar age with subtraction of residual dose after 4 h exposure to bright sunlight in summer.

Figure 5 and overdispersion values in Table 4 show that the measured quartz medium aliquots have more heterogeneous dose distribution than in the case of K-feldspar small aliquots. As it can be supposed that the dated sediments were well bleached before burial, the more heterogeneous distribution of De-s in quartz is probably caused by the heterogeneity in the environmental beta dose rate. This can be the result of the microscopic fluctuations in the spatial distribution of feldspar containing beta emitter 40K (Mayya et al., 2006). In addition, the different amounts of radioactive inclusions in the quartz grains, which lead to a small internal alpha dose rate (Galbraith and Roberts, 2012), cause heterogeneous distribution of internal dose rates.

Post-IR IRSL290 measurements on K-feldspar

Every measured aliquot of K-feldspar showed a good recycling ratio in the range of 1.0±0.1, and except three rejected aliquots they had recuperation under 5%. Residual doses after 12 h bleaching under changeable sunlight in winter are about 7–19 Gy on average (Table 4), while after the same duration of bleaching under bright sunshine in summer are about 3–5 Gy on average (which correspond to 13–28% and 4–10% of the mean natural equivalent doses respectively). The dose recovery ratios changed between 0.79 and 1.14 (from 0.96±0.14 to 1.1±0.04 on average, Table 3), but, the poor dose recovery ratio of post-IR IRSL290 signal of K-feldspar does not necessarily mean an inaccurate measurement of De (Buylaert et al., 2012). The fading test of these samples indicates relatively low fading rates or g-values between 0.95 and 1.48%/decade (1.26±0.21%/decade on average). The fading experiments of Thiel et al. (2011) indicated that the small fading rate of post-IR IRSL290 signal of K-feldspar may be a laboratory artefact. Therefore, fading correction was not applied. Feldspar dating of the non-saturated samples is based on equivalent doses of 9–12 aliquots per sample. Their De values show lower relative error (2.5–6%), higher precision (17–40), and lower dispersion than in the case of the quartz fractions of the same samples. The distributions of the equivalent doses are more or less symmetric and their kernel density estimate curves show one De population. Two representative examples are presented in the abanico plots of Fig. 5 B and D. The relatively small overdispersion of the De values (between 4% and 12% on average, Table 4) probably indicate well-bleached sediments at the time of deposition according to Olley et al. (2004). The difference between the mean and the central equivalent doses is a maximum of 1%. Hence, the ages were calculated by the mean De values.

Two samples (Nt1 and Nt2) are saturated as their natural post-IR IRSL290 signals (Ln/Tn) lie above the saturation level. The minimum age of these samples was calculated with the 2*D0 values, which correspond to approximately 86% of the dose-response curve (Murray et al., 2014).

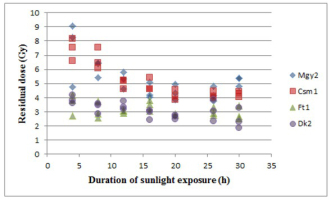

In the bleaching experiment in natural sunlight during summer the measured post-IR IRSL290 residual doses of the four K-feldspar separates (Mgy2, Csm1, Ft1 and Dk2) ranged from 3.6±0.4 Gy to 7.4±0.5 Gy after 4 h exposure to bright sunshine, then they decreased more slowly with some scatter, and they were between 3.0±0.1 Gy and 5.2±0.6 Gy after 12 h exposure to sunshine, then an unbleachable component ranged from 2.5±0.7 Gy to 5.2±0.3 Gy after 30 h exposure to bright sunshine. The latter corresponds to 3–8% of the measured K-feldspar post-IR IRSL290 natural doses. K-feldspar of samples Mgy2 and Csm1 bleached slightly more rapidly than that of samples Dk2 and Ft1 (Fig. 6). Residual doses measured after 12 h exposure to changeable sunshine in winter varied from 7.4±1.0 Gy to 19.2±3.0 Gy and correspond to about 13–28% of the measured K-feldspar post-IR IRSL290 natural doses.

Fig 6

Change of post-IR IRSL290 residual doses of four K-feldspar separates due to exposure to bright sunlight in summer. (The measured average natural doses are 100 Gy in Mgy2, 115 Gy in Csm1, 35 Gy in Ft1 and 36 Gy in Dk2.)

Except for one sample (Mgy2), the feldspar ages without residual dose subtraction are older than the quartz ages of the same samples, and the ratio of them range between 1.01±0.10 and 1.31±0.14 (Table 4). But, taking into account the 1 sigma error the two sets of ages agree in the case of samples Mgy1–2, Csm1–4 and Ft1–2, while the K-feldspar ages of samples Dk1–5 agree within 2 sigma error limit with quartz ages.

Using the same post-IR IRSL290 protocol on coarse-grain feldspar, there are some published data of residual doses, e.g. Alexanderson and Murray (2012) measured about 12 Gy residual dose in glaciofluvial sediments after 5 h bleaching in solar simulator in samples with 20–55 Gy natural dose; t6 et al. (2012) and Buylaert et al. (2012) detected about 2 Gy and 5±2 Gy residuals in modern analogues of shallow marine and coastal sediments, respectively. Dating coarse-grain (0.16–0.25 mm) feldspar of coastal dune, Preusser et al. (2014) observed that prolonged (several days) daylight exposure leads to systematic, but only slightly lower residual De values. Ito et al. (2017) found unbleachable residual doses, and they subtracted it before age calculation. In their experiments, coarse-grain (0.18–0.25 mm) K-feldspar of beach sand was bleached under artificial sunlight up to 800 h, and the residual dose decreased from 15.7±1.8 Gy to 2.8±0.2 Gy. But, Colarossi et al. (2015) detected monotonic decrease of post-IR IRSL signals during 14 days exposure to artificial light in a solar simulator and did not find any unbleachable residual signal. In long-term (>80 days) laboratory bleaching experiments Yi et al. (2016) measured 6.2±0.7 Gy residual dose by post-IR IRSL290. This residual dose was constant, or very difficult to bleach after ~300 h exposure to light in a solar simulator.

Some experiments, e.g. Buylaert et al. (2011), Li et al. (2013) and Preusser et al. (2014) proved that the residual dose increases with the increase of stimulation temperature, and presumably it mainly arises from thermal transfer effects due to preheat temperature (Buylaert et al. 2011).

Our bleaching experiment in bright sunlight in summer gave similar results (between 2.5±0.7 and 5.2±0.3 Gy residual doses after 30 h bleaching) to most of the above mentioned earlier studies, among them, the outcomes of residual measurements of Thiel et al. (2012) and Buylaert et al. (2012) on modern sediments.

Quartz OSL and K-feldspar post-IR IRSL290 ages of the dated sediments

In the southern part of the study area at Nagytarcsa, the fluvial gravelly sand layers of Danube terrace V, which contain saturated quartz and feldspar, are older than ~ 296 ka according to feldspar post-IR IRSL290 minimum age based on 2*D0 values. Therefore, they were formed earlier than the MIS 7 period. This minimum age is not in conflict with the traditional terrace chronology of Pécsi (1959), Kretzoi and Pécsi (1982), and the 800 ka minimum age (Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger et al., 2005a). The equivalent terrace in the Gerecse Hills developed between 2.4 and 1.0 Ma ago (Csillag et al., 2018).

In the central part of the Pest Plain, the two aeolian fine sand layers on terrace V in the Mogyoród gravel mine are about 37–38 (±3) ka old based on quartz ages (Table 4). In the case of the lower sample, the K-feldspar post-IR IRSL290 age without the subtraction of any residual dose and the quartz OSL age are in excellent agreement and their ratio is 0.99±0.10. Consequently, after residual dose subtraction, the ratio between feldspar and quartz ages are 0.80±0.08 and 0.92±0.09, depending on the bleaching conditions. In the upper sample, the age of feldspar without residual subtraction is older than the quartz age, while after the subtraction of the winter residual dose, it is younger than the quartz, the ratio of the feldspar age to quartz age is 1.10±0.11 and 0.94±0.10, respectively (Table 4).

Here, the ages of the dune sand samples indicate wind activity in the cold and dry period of MIS 3 on the surface of terrace V. Aeolian sediments with similar ages were identified in other parts of Hungary, e.g. the ~39 ka old wind-blown sand in the southern part of Hungary at Katymár (Sümegi et al., 2019, Fig. 1), the 41±0.8 ka and 35±5 ka old loess west from the study are at Süttő (Novothny et al., 2010b), and 37–38 (±3) ka old loess layers south from the study area at Paks (Thiel et al., 2014; Fig. 1). In the other part of the Mogyoród gravel mine relict, sand-wedge polygons were studied as well earlier, and the infill sediments of a sand-wedge were 16–17 (±2) ka old, dating with quartz OSL method (Fábián et al., 2014).

In the northern part of the study area, on terrace III, the dated two aeolian silty fine sand samples in the East wall of the Csomád sand mine, deposited 43±4 and 39±3 ka ago in MIS 3, according to the quartz OSL ages. The post-IR IRSL290 age of feldspar without residual-subtraction is similar to the age of quartz in the lower sample. In the case of the upper sample, the quartz age is between the age of feldspar without residual subtraction or with the subtraction of the summer residual dose after 4 h exposure to bright sunlight and the feldspar age after the subtraction of the winter residual dose. The last one is the closest to the quartz age, their ratio is 0.96±0.10 (Table 4).

The ages of the quartz in the fluvial sand samples in the West wall of this mine are 31±3 and 29±3 ka. The feldspar without residual subtraction gives older ages than the quartz with ratio 1.14±0.12 (Csm4) and 1.09±0.12 (Csm3). Meanwhile, after winter residual dose subtraction, the feldspar ages are younger, they are 0.94±0.10 (Csm4) and 0.88±0.10 (Csm3) of the quartz ages.

The ages of the dated samples in this mine indicate the formation of a sand dune in MIS 3, and fluvial sedimentation of a small stream about the transition from MIS 3 to MIS 2 on the surface of terrace III, which was formed minimum 170 ka ago (Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger et al., 2005a). This 39–43 (±4) ka old dune sand and the coeval loess in the area of Süttő and Paks (Novothny et al., 2010b, Thiel et al., 2014 respectively) prove strong wind activity in a cold and dry climate period of MIS 3. The fluvial sediments of a small stream at Csomád probably deposited during the warmer period at the end of MIS 3 or at the beginning of MIS 2 because chernozem-like soils formed about those times in the Katymár loess-paleosol sequence (Sümegi et al., 2019).

In the Fót sand mine, also on the area of terrace III, the dated lower and upper sand layers of the slope sediments with reworked fluvial material, deposited during the MIS 2 period, 23±2 and 15±1 ka ago, based on quartz dating. The relation between the feldspar and quartz ages shows similar tendencies to most of the other dated samples. The feldspar ages without residual subtraction are older than the quartz ages with ratios 1.07±0.10 and 1.05±0.10, while they are younger than the quartz after winter or summer residual subtraction, with ratios 0.83±0.08, 0.81±0.08 and 0.94±0.09. The lower slope sediment was probably deposited during cold period, in the Last Glacial Maximum, because loess layers with similar ages were dated to the same periods at Katymár (~22.5 ka BP, Sümegi et al., 2019) and Süttő (22±2 ka, Novothny et al., 2011).

On terrace IIb, in the Dunakeszi sand mine, fluvial sand layers of a stream were deposited about 15–16(±1) ka ago, and the age of the sand layers in a dune is about 14±1 ka, according to quartz dating. Here is the largest difference between the feldspar ages which were calculated without residual dose subtraction and the quartz ages, the ratio of them ranges from 1.21±0.12 to 1.31±0.14 (Table 4). The feldspar ages after winter residual dose subtraction are younger than the quartz ages (feldspar age/quartz age is 0.87±0.09 – 0.96±0.10) except for the uppermost sample. Meanwhile, the feldspar of sample Dk2 after the subtraction of the summer residual dose gives an older age than the quartz does. The ages of the dated stream sediments and dune sands prove fluvial, and then aeolian activity during MIS 2 on the surface of terrace IIb, which developed a minimum 100 ka ago. In the southern part of the study area, fluvial sand with a similar age (~16 ka) was dated by TL method at Dunavarsány (Fig. 2; Ujházi et al., 2003; Gábris, 2003). 14 ka old dune sand was detected by the help of radiocarbon and luminescence dating in terrace IIa on the Szentendre Island at Kisoroszi (Fig. 2; Ujházi et al., 2003; Gábris, 2003), in the Gödöllő Hills (Fig. 1) at Tura (Novothny et al. 2010a), and on other areas of Hungary as well, e.g. on the Nyírség alluvial fan (Fig. 1; Lóki et al., 1994; Gábris, 2003; Buró et al., 2014; Kiss et al., 2015).

The 15-16(±1) ka old stream sediments of the Dunakeszi sand mine probably were deposited during the Oldest Dryas and the Allerød-Bølling interstadial, while the formation of the 14±1 ka old dune corresponds to the colder and drier period of the Allerød-Bølling according to the climate reconstruction of Kiss et al. (2015) with regards to Hungary.

Taking into account the differences between the ages of the dated two minerals, to get the same feldspar ages as the quartz ages, the assumable residual doses of the feldspar are set to be between 0 and 15±1 Gy (Csm1) or 0 and 24±2% (Dk1) of the measured natural doses (Table 4). These results imply that in most cases it is necessary to subtract some residual dose from the measured natural dose of feldspar before age calculation.

. Conclusions

Optically stimulated luminescence dating of sandy fluvial, aeolian and slope sediments, collected on the Danube terraces of the Pest Plain serves new ages for this area where the numerical age data and the palaeontological findings are very scarce. Moreover it gives an opportunity for the comparison of coarse-grain quartz OSL and K-feldspar post-IR IRSL290 ages of the same sediments.

The measured quartz medium aliquots show more heterogeneous dose distribution than the K-feldspar small aliquots. Probably, this is caused by the heterogeneity in the environmental beta dose rate and the internal alpha dose rate.

The feldspar post-IR IRSL290 ages without residual dose subtraction are older than the quartz OSL ages, except for one sample, which quartz and feldspar ages are almost identical. But, the two sets of ages are overlapping within 1 or 2 sigma error.

Our bleaching experiment showed that the residual dose of feldspar is from 2.5±0.7 Gy to 5.2±0.3 Gy or 3–8% of the measured natural dose after 30 h exposure to bright sunshine. Based on comparison with the quartz ages the assumable residual doses range from 0 Gy to 15±1 Gy and amount to 24±2% of the measured natural doses. Therefore, in most cases of our samples, some residual dose subtraction is necessary before the calculation of the post-IR IRSL290 ages. However, without quartz OSL age data, or independent age control, the value of the residual dose of feldspar is uncertain. But, the range between the feldspar post-IR IRSL290 age without residual-subtraction, and the residual-subtracted age, can be considered as the maximum age range of the sediment. For subtraction, the residual dose after 4 h exposure to light in a solar simulator or bright sunshine is favourable, because the post-IR IRSL290 signal decreases rapidly in this time period.

The minimum age of the dated fluvial gravelly sand of terrace V is ~ 296 ka based on 2*D0 values of feldspar post-IR IRSL290. This age does not contradict the traditional terrace chronology and the earlier published age data of this terrace. The other studied sediments on the surface of the terraces V, III and IIb were deposited much later than the formation of the terraces. They indicate deposition of sediments in MIS 3 and MIS 2 periods: aeolian activity at 43–37(±3) ka and 14±1 ka ago, and fluvial sedimentation of small streams about 31–29(±3) ka and 16–15(±1) ka ago. The new ages help to reconstruct the surface developments of the Danube terraces. The age of the dated dune sands with coeval aeolian sediments in Hungary indicates the cold and dry periods with strong wind activity of the Late Weichselian.