. Introduction

A large number of tree-ring chronologies were devel-oped for the boreal zone and subarctic forest-tundra eco-tone in the northern hemisphere (Jacoby and D’Arrigo, 1989; Briffa et al., 2001; Esper and Schweingruber, 2004; D’Arrigo et al., 2008; Büntgen et al., 2011). Trees growing in the vicinity of a longitudinal tree line (ecotone) are very sensitive to environmental conditions and thus we are able to assign the response of the tree growth to climate (Jacoby et al., 1982; Briffa et al., 2004). The dendrochronological research north of the tree line is difficult due to the absence of trees and is limited to only few shrub and dwarf shrub species. However, in recent years there has been a great interest in obtaining dendroe-cological data from these plants because the High Arctic is well recognized to be highly sensitive to contemporary and future climate change (Woodcock and Bradley, 1994; Schmidt et al., 2006; Zalatan and Gajewski, 2006; Owczarek, 2009; Forbes et al., 2010; Hallinger et al. 2010, Owczarek et al., 2013; Schweingruber et al., 2013; Myers-Smith et al., 2015a). In comparison with trees, dwarf shrubs produce extremely narrow and discontinuous growth rings, and missing rings are a common feature (Schweingruber and Dietz, 2001; Schweingruber and Poschlod, 2005; Bär et al., 2006; Buchwal et al., 2013). Earlier Arctic dwarf shrub research was mainly focused on age estimation and the analysis of wood anatomy (Warren-Wilson, 1964). Woodcock and Bradley (1994) showed the potential of arctic willow (Salix arctica Pall.) growth ring variation for dendroclimatological analyses. However, the first methodological procedure for the den-droecological dwarf shrub analysis was provided by Bär et al. (2006). Bär et al. (2006, 2007) constructed the first ring width chronologies of alpine dwarf shrub black crowberry (Empetrum hermaphroditum L.) from the Norwegian part of the Scandinavian Mountains. Rayback and Henry (2005) as well as Weijers et al. (2010, 2012) used growth increments from the internode length of white Arctic mountain heather (Cassiope tetragona L.) as the climate proxy records. Of these, Weijers et al. (2012) constructed the longest chronology, of nearly 200 years, for the High Arctic. Most dendroclimatic studies emphasise the temperature signal recorded by the growth ring of dwarf shrub but the new data shows the possibility to also reconstruct moisture stress during the growing season (Bloket al., 2011; Rayback et al., 2012).

Further analyses in the Arctic are necessary due to sparse and short meteorological station records. Temperature has been observed almost continuously in Svalbard since 1898, however, in other parts of the archipelago continuous meteorological observations are shorter, e.g. since 1978 in southwestern Spitsbergen. Increase of temperature and changes of other climatic variables over the last few decades are evident by meteorological data in this area. According to the latest Global Climate Models (GCM) and Regional Climate Models (RCM) results, it is predicted that the air temperature in the Arctic will have increased between 5°C and 10°C in winter and 0°C and 2°C in summer during the next 100 years. New models simulate for almost all parts of the Arctic the increase of precipitation by 20–50% (Brönnimann, 2015; Przybylak, 2016). Dendrochronological research in different parts of the Arctic may be helpful for better understanding of temperature and moisture trends. Polar willow (Salix polaris Wahlenb.) is one of the few species in the Norwegian High Arctic archipelago of Svalbard which can be used in dendrochronological studies. In the southern part of Spitsbergen, the largest island of the archipelago, such research has not been carried out so far. Our new data can improve the Arctic dendrochronological network. The aims of this study were: (1) to construct polar willow growth ring chronology for the southwest Spitsbergen, (2) to indicate and explain the origin of extremely low value of annual growth (pointer years) in tree-ring record of polar willow from the Hornsund area.

. Study Area

Location and climate

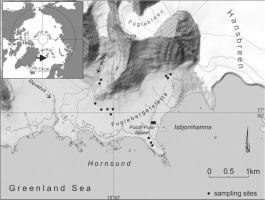

The study area is located in the southwestern part of Spitsbergen specifically the Svalbard Archipelago (Fig. 1). A large part of this High Arctic island is covered with glaciers, which are in the phase of accelerated retreat (Hagen et al., 2003; Błaszczyk et al., 2013). A predominant feature of the research area is high mountain relief with extensive talus cones and debris flow tracks (Owczarek 2010; Owczarek et al., 2013). This part of Spitsbergen is comprised of metamorphosed Precambrian and Lower Palaeozoic rocks (amphibolites, mica schists and quartzites), known as the Hecla Hoek Succession (Manecki et al., 1993). Typical landforms of the non-glaciated areas are coastal plains with several marine terrace levels of various ages located at the elevation of 2-230 m a.s.l. (Lindner et al., 1991) (Fig. 2). Present-day glacier forefields are being rapidly transformed by paraglacial processes (Owczarek et al., 2014a). The active layer within the lower levels of the raised marine beaches reaches maximum depth of 1.3 to 2.0 m depending on the types of the ground and weather conditions in each particular season (Leszkiewicz and Caputa, 2004; Migała et al., 2004).

Fig. 1

Location map showing the sampling sites in the southwestern Spitsbergen in the vicinity of the Polish Polar Station in Hornsund.

Fig. 2

General view on the typical sampling area in northwestern shore ofHornsund fjord; flat raised marine terraces with tundra vegetation are visible in the foreground.

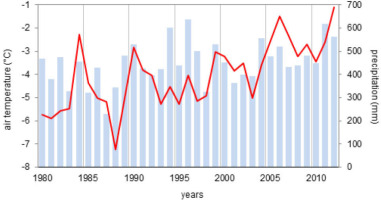

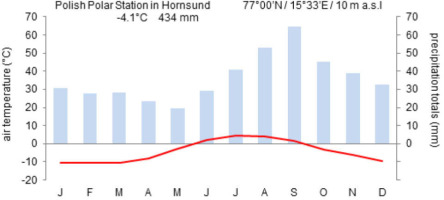

Spitsbergen has a periglacial climate often referred to as the "High Arctic climate" (Przybylak, 2016). Over the last 30 years, mean annual air temperature in the Hornsund area has varied from –7.4°C (1988) to –1.5°C (2006) with an average of–4.2°C (Marsz and Styszyńska, 2013; Hornsund GLACIO-TOPOCLIM Database, 2014). Inter-annual fluctuations of temperature are typical of this area but a distinct warming trend is evident. Nordli (2010) has calculated air temperature trends for about the last 100 years in Svalbard, which is +0.24°C per decade, but during the last 30 years the growth has been faster (+1.1°C per decade) (Marsz and Styszyńska, 2013) (Fig. 3). The annual total precipitation in this area is 434 mm/year (1979–2012). The extreme daily totals are observed in August and September (43–58 mm) (Hornsund GLACIO-TOPOCLIM Database, 2014). The growing season in this part of Spitsbergen is restricted to three months and usually begins in the first half of June when the ground temperature first exceeds 0°C (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3

Course of annual mean air temperature and precipitation totals in the Polish Polar Station, Hornsund (77°N, 15°E) (source: Marsz and Styszyńska, 2013).

Fig. 4

Summary of climate at the meteorological station in the Polish Polar Station, Hornsund (77°N, 15°E) (source: Marsz and Styszyńska, 2013).

Polar willow ecology

Different tundra plant communities occur in the non-glaciated parts of Spitsbergen. Four plant zones are distinguished on which of the following species dominates (Rønning, 1996): white Arctic mountain heather (Cassio-pe tetragona L.), mountain avens (Dryas octopetala L.), Svalbard poppy (Papaver dahlianum Nordh.) and polar willow (Salix polaris Wahlenb.). The Salix polaris zone is best developed on the northern coast of the Hornsund fjord, where it covers raised marine terraces. Besides polar willow and net-leaved willow (Salix reticulata L.), the community mainly consists of purple saxifrage (Saxi-fraga oppositifolia L.) and different species of mosses and lichens.

Polar willow (Salix polaris) is a deciduous, prostrate, creeping shrub, usually less than eight cm tall (Påhlsson, 1985). It grows in different locations, but favours flat gravel areas and wet depressions (Rønning, 1996). This plant forms extensive mats often together with other species, for example purple saxifrage and different species of mosses. Only the oval, dark green leaves with short green shoots are visible above the ground (Fig. 5a). Wooden branches and the root system of polar willow are located underground, in the uppermost part of the permafrost active layer. The diameter of the branches does not exceed 1.2 cm. This dwarf shrub has well-defined growth rings with boundaries delimited by one or more rows of cells (Fig. 5b) (Owczarek, 2009; Owczarek et al., 2013).

Materials and Methods

Field sampling

Complete individuals of Salix polaris, including their root and branch systems, were collected during the short Arctic summer seasons in 2007, 2008, 2011 and 2012. The total of 45 samples of polar willow from 10 sites were collected from the flat raised marine terraces at the elevation of 12–28 m a.s.l. in the vicinity of the Polish Polar Station in Hornsund (Fig. 1). Each individual was documented in a digital photograph. Each sampling point was situated on relatively homogeneous surface, that does not show clear evidence of periglacial activity (e.g. soli-fluction lobes). The sites were flat and well-drained, never in local depressions, channels or on steep edges. Each collected individual was cut with pruning shears and placed in string bags. To protect the samples, the bags were filled with a mixture of ethanol and glycol.

Sample preparation and analysis

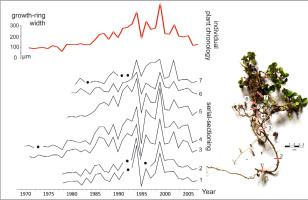

The collected samples were sectioned with GSL 1 sledge microtome. The 15–20 μm cross-sections were taken along each individual from four to seven different places (depending on the length of the root and wooden branches) in order to develop their chronology (Fig. 6). This method was described in detail in previous research (e.g. Bär et al., 2006; Hallinger et al., 2010; Owczarek et al., 2014a; Myers-Smith et al., 2015b). In the laboratory, microtome cross-sections were prepared from the whole stem diameter of the selected segments. After staining with 1% solutions of safranin and astra blue dyes, digital photographs of the micro-sections were taken for tree-ring analyses. The width of rings distinguished in the collected individuals ranges from relatively wide 0.8 mm, to extremely narrow of less than 0.01 mm (Fig. 5b). Partially or completely missing growth rings are very common in the analysed specimens.

Fig. 6

Individual plant chronology of 38 year old Salix polaris created on the basis of serial sectioning (after Owczarek et al. (2014a) modified).

Chronology development and analysis of extreme years

The Salix polaris measurements followed the standard dendrochronological procedures (Cook and Kairiukstis, 1990 and Speer, 2010). The ring widths were measured along two or three radii using the OSM 3.65 and PAST4 software (VIAS, 2005). The TSAP software was used for visual cross-dating of growth width series, and the COFECHA software for the statistical quality control of cross-dating (Holmes, 1983). Locally absent or wedging rings were examined by applying serial sectioning for each individual (Fig. 6) (Kolishchuk, 1990).

In general, the raw data fluctuated around a horizontal straight line, without a distinct age trend. Therefore the measurements were transformed into chronology by averaging. The ARSTAN (ver.41d) standardisation software was used to calculate the chronology and its parameters (Cook, 1985). In order to compare the resulting chronology with other chronologies and to assess its reliability and relevance for the dendroclimatological research, the appropriate descriptive statistics, including mean sensitivity (MS), mean series inter-correlation (Rbar) and expressed population signal (EPS), were calculated (formulas after Wigley et al. (1984) and Speer (2010)). In the standardised dendrochronological data, the extreme years were distinguished using the threshold value of ±1 standard deviation. In the next step the distinguished negative years were compared with climatic variables. The meteorological data from the Hornsund station, covering the period 1978–2011, were obtained from Marsz and Styszyńska (2013) and Hornsund Database (2014). The climate variables investigated in this study included the monthly data: mean air temperature (°C), mean maximum diurnal air temperature (°C), mean minimum diurnal air temperature (°C), monthly absolute maxima of air temperature (°C), monthly absolute minima of air temperature (°C), number of days with positive mean diurnal air temperature, sunshine duration (hours), percentage of relative sunshine duration, total monthly precipitation (mm), monthly mean thickness of snow cover (cm) and number of days with snow cover. In addition we used daily air temperature and precipitation data for the selected years.

Results

Tree-ring chronology

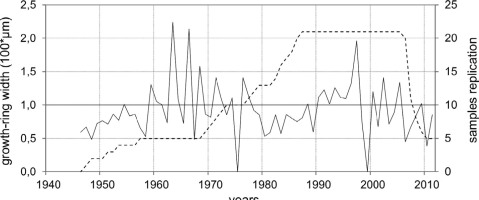

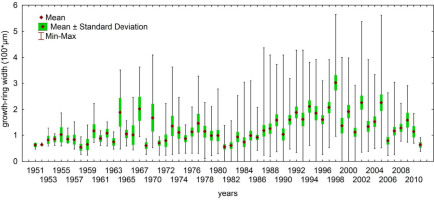

Finally, 21 out of the 45 samples were included in the chronology and became the basis for further analyses. The remaining sequences were removed due to a large number of missing rings, eccentricity, presence of scars and clearly visible reaction wood. The oldest individuals of Salix polaris used in the chronology construction were 62 years old, while the mean plant age was 38. After truncation up to minimum three series, the constructed chronology covers the years 1951–2011 (Table 1, Fig. 7). The annual increments are in general very narrow and vary between 18 μm/yr to 564 μm/yr, with the mean approx. 137 μm/yr. In the course of the sample curves of the dwarf shrub no age trend is observed, as is in the case of trees. In general, from the beginning of the 1980s an increase of the mean and maximum growth ring width is observed (Fig. 8). Increase in temperature of 1.1°C per decade and 43 mm of annual precipitation per decade is accompanied by positive trend in growth ring width (12 and 35 μm for mean and maximum growth ring width, respectively) (Table 2). The reduced growth ring width over the last five years is a result of unequal samples replication in comparison to the previous three decades. In the detailed course of the chronology curve a decline can be observed in the 1980s (Fig. 7). The periods of increased growth rate can be noticed in the 1970s and 1990s.

Table 1

Statistics for polar willow growth-ring chronology.

Fig. 7

Growth-ring chronology of Salix polaris (solid line) and its sample replication (dashed line).

Fig. 8

Mean, minimum and maximum grow-ring widths variability of Salix polaris samples used in the constructed chronology.

Table 2

Values of trend coefficients of climate and tree-ring variables and their statistical characteristics.

The developed chronology shows very high inter-annual variations expressed by quite a high value of the mean sensitivity (0.56) (Table 1). The Expressed Population Signal values were slightly below the 0.85 threshold (Wigley et al., 1984), and their mean value for the whole chronology was 0.82 (this value decreased in the oldest part of the chronology). This means that in order to reduce the reconstruction uncertainty in the future it will be necessary to increase the sample size (number of plants), especially of the oldest individuals.

Interpretation of extreme years

Consistent extreme years (narrow or wide ring widths) could be distinguished on many sections and in the resulting chronology. We found 13 extreme years in the Hornsund chronology, of which nine were negative: 1958, 1967, 1975, 1980, 1981, 1989, 1999, 2006 and 2010, and four were positive: 1963, 1966, 1976 and 1997. Positive years are usually the effect of regeneration after unfavourable conditions in the previous years. Negative years are much more important for dendroclimatological and ecological analyses, indicating unfavourable environmental conditions. Interpretation of extremely low growth or even a missing ring on the basis of existing meteorological data for the Hornsund station showed that there is no a single factor influencing growth of polar willow.

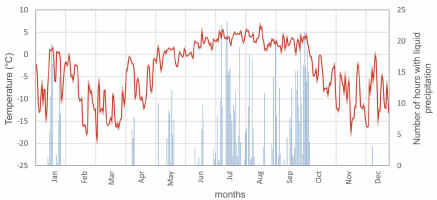

Detailed interpretation of the extreme years showed that very narrow rings occur when a few unfavourable climatic factors before or during the year of ring formation act together (Table 3). Despite the fact that there were not enough observational data for the years 1958, 1967 and 1975, we can trace the course of the weather in subsequent extreme negative years since 1978. In the year 1980 low annual air temperature of the previous year and the second largest absolute minimum of the air temperature were accompanied by a number of days with positive mean diurnal air temperature during winter. Such thermal fluctuations could have damaged the plant tissue and previous year's shoots. Another threat for the dwarf shrubs in 1980 was very low precipitation that spring (May-June). Similar meteorological situations, i.e. the occurrence of a number of days with positive temperatures in winter, were observed in 2006. That year had up to 13 days with positive temperature in January and the highest absolute maximum of air temperature in January (4.9°C) recorded for Hornsund. Despite the high precipitation in January 2006 (321% of the norm for the reference period, 1978–2011), the above average temperatures led to fast snow melt and consequently very low mean thickness of snow cover in January. The lack of any substantial snow cover along with the lowest recorded absolute minimum of air temperature (–35.9°C) that same month, could have caused damage to the dwarf shrubs, and thus explain the very narrow ring produced later that year. Additionally, the lowest recorded absolute minima of air temperature in May and June of that same year (2006) and the lack of snow cover at that time would have caused a water shortage for plants and thus also explain the formation of a very narrow ring. In 2010, a rapid thaw took place in January, an effect of nine days with positive temperature. Additional occurrence of liquid precipitation resulted in only 26 days with snow cover. After episodes of snow melt, a rapid temperature drop took place (Fig. 9). Lack of a deep and stable snow cover which isolates and protects Salix shrubs against frost damage resulted in a very narrow growth ring formation that year.

Table 3

Climatic conditions of the negative pointer years.

Unfavourable climatic conditions marked grey

Fig. 9

Annual course of daily mean air temperature and number of hours with liquid precipitation in 2010 in the Polish Polar Station, Hornsund (GLACIO-TOPOCLIM Database, 2014).

The reason for extremely narrow growth of polar willow could have also been very low precipitation at the beginning of the growing season accompanied by a lack of snow cover, which severely restricted water availability to the shrubs and resulted in the formation of a very narrow ring. Low amount of spring precipitation is rather typical for this area but exceptional years with values, which are significantly below the average, can be distinguished. The growing periods for Salix communities are determined based on the start of daily temperature T > 0°C. Although Kappen (1993) reported, that vascular plants can be active under snow, no photosynthesis is observed if the ground is frozen. Such weather conditions occurred, for example, in 1989, when there was a low annual air temperature the previous year, followed record lowest precipitation in May 1989 and a lack of snow cover the next month. Also, a similar weather pattern occurred in 1999, with low (snow) precipitation during that winter and spring, and in fact the lowest annual snow-cover thickness of the whole instrumental record (1978–2011). Development of narrow rings in 1989 and 1999 as an effect of physiological drought connected with low winter precipitation can be linked to more complex weather conditions. Other factors like predominance of anticyclonic circulation at the beginning of the 1989 vegetation period (Niedźwiedź, 2006) and relatively high June temperature during these years (respectively 2.3°C and 2.6°C mean monthly air temperature when the average for the period 1978–2011 is 1.9°C) led to increase of evaporation and soil desiccation.

In addition, most of the extreme years were characterised by very low (above average for the reference period) sunshine duration in summer (Table 3). Sunshine is not the growth limiting factor at this site, but its values are connected to temperature, which logically drives the tree growth during the polar summer.

Discussion

What was received in the course of the study is a 61-year-long chronology, which is similar to the results from the other parts of the Arctic (Woodcock and Bradley, 1994; Zalatan and Gajewski, 2006; Forbes et al., 2010; Buchwal et al., 2013; Schweingruber et al., 2013). The obtained EPS value, which is a measure of the common variability in a chronology, was also similar to the results of other shrubs studies: 0.58–0.90 for Betula nana (Blok et al., 2011), 0.69 for Cassiope mertensiana (Rayback et al., 2012), 0.79–0.86 for Salix polaris (Buchwal et al., 2013), and 0.83–0.97 for Salix pulchra (Blok et al., 2011). However, in some studies stable values higher than the threshold were obtained: 0.87-0.88 for Em-petrum hermaphroditum (Bär et al., 2006) and 0.98 for Salix lanata (Forbes et al., 2010).

The extensive warming and changes in precipitation of the Svalbard archipelago during the last few decades correlates with the increase of growth rings width. These data confirm the observations over the Arctic areas where the fast expansion of tundra shrubs is observed (Forbes et al., 2010; Blok et al., 2011; Callaghan and Tweedie 2011 and Tremblay et al,. 2012).

During the last few years there has been a significant progress in the development of the Arctic plants chronologies. However, synchronisation of these chronologies can be difficult due to ecological disturbances, for example the impacts of microtopography, microclimatic differences, soil conditions, influence of animals, insect defoliation (Büntgen and Schweingruber, 2010). Therefore there is a need for developing numerous site chronologies from different parts of the Svalbard archipelago in order to recognise common growth patterns that can be associated with climate variability. Southwestern Spitsbergen, due to its location on the southern edge of Svalbard archipelago, is an important area for climate reconstruction and prediction in the High Arctic. It should be added that some extreme pointer years reconstructed in this study are in accordance with those from different parts of the Arctic (Fig. 10). The negative years 1980–1981 in this study can also be observed in S. arctica chronology from Ellesmere Island (Woodcock and Bradley, 1994), S. polaris from the central part of Spitsbergen (Buchwal et al. 2013) and S. lanata from the coastal zone of the northwest Russian Arctic (Forbes et al., 2010). The negative year 1968 in this study is also apparent in the chronologies of S. lanata from the Russian Arctic and S. alaxensis from the Western Canadian Arctic (Zalatan and Gajewski, 2006). Also in the case of the positive years, consistent years can be distinguished in many arctic regions. For example, a very wide ring of 1997 found in the S. polaris chronology (this study) was also found in Em-petrum hermaphroditum in the Norwegian part of the Scandinavian Mountains (Bär et al., 2006), while a wide ring of 1967 is also present in the chronology of S. lanata (Forbes et al., 2010) and S. alexensis (Zalatan and Gajewski, 2006).

Fig. 10

Tree-ring chronologies for different location of North Atlantic sector, including southwestern Spitsbergen and north coast of Eurasia: A — Salix polaris from Svalbard (this study), B — Betula pubescens from Troms Region, northern Norway (Opala et al. 2014), C — Salix lanata from Nenets Autonomous Okrug, northwest Russia (ITRDB, 2015a and Forbes et al., 2010), D — Pinus sylvestris from Kola Peninsula, northwest Russia (ITRDB, 2015b and Gervais and MacDonald, 2000). Black circles indicate negative pointer years common within all chronologies. Red circles indicate negative pointer years present only in single locations (not observed in Hornsund site).

The results of this study support the "snow-shrub hypothesis" developed in earlier studies in the Arctic (Hal-linger et al., 2010; Schmidt et al., 2010 and Mallik et al., 2011), that deep snow cover is important to protect Salix shrubs from frost damage and provide a water reservoir by snow melt during the growing season. These papers indicate the influence of winter precipitation on shrub growth. The positive impact of deeper winter snow on shrub growth was also experimentally demonstrated on the example of Cassiope tetragona in the Advent Valley in Central Spitsbergen (Blok et al., 2015). The seasonal temperature fluctuation, type of soil and type of tundra community influence on active-layer thickness, the upper part of which is penetrated by dwarf shrub roots. The depth of thaw determines water drainage, nutrient migration and water absorption (Migała et al., 2014). Calaghan et al. (1993) reported that Salix polaris tolerates very short growing seasons and long periods of winter snow cover, and the development of these plant is strongly related to water availability and temperature. Our research confirms these observations. The negative influence of the positive temperature values during winter months can be linked to the melting snow cover and the development of a thin ice cover, which can partially damage the previous year dwarf shrub branches. Bokhorst et al. (2009, 2012) reported similar data, that dwarf shrubs in the Arctic area are negatively impacted by extreme warming events during winter.

Strong positive correlation of growth ring width with summer temperature was not observed in the Hornsund area (Owczarek et al., 2014b). Positive correlation with precipitation was noted in a few parts of the Arctic (Holzkämper et al., 2008 and Blok et al., 2011). However, the dominant influence of summer temperature was described in other regions, e.g. in Central Spitsbergen (Buchwal et al., 2013) and East Greenland (Büntgen et al., 2015). The presented results indicate the effect of many climatic factors acting together, with significant influence of climate extremes. The occurrence of these extremes is concurrent with the dendrochronological pointer years for the analysed polar willow.

Non-climate factors can also affect growth ring widths, and the resulting chronology curve, independent of climate. The influence of the geomorphological processes on the growth ring width of the dwarf shrub, reported by Owczarek et al. (2013), was reduced in this study, because the samples were collected from the flat raised marine terraces. The disturbances observed in 2005 and 2006 were connected with the insect outbreaks noted in 2005 in different parts of the Arctic (Hallgrímsson et al., 2006; Jepsen et al., 2013 and Halldórsson et al., 2013). Despite the fact that the 2006 was the warmest year during the observation period in this part of Spitsbergen, the growth ring widths during these years were relatively small, which may also be due to insect damage. Epstein et al. (2013) mentioned that the insect outbreaks are an important factor for the recent dynamics of the tundra vegetation.

Conclusions

– During the last decade there has been a significant increase in the number of the Arctic plants chronologies due to a high sensitivity of tundra vegetation to modern climate change. However, synchronisation of these chronologies can be difficult due to local site influences. Therefore, there is a need for developing numerous site chronologies from different parts of the High Arctic in order to recognise a common growth pattern that can be associated with climate variability.

– Salix polaris is one of the species from southwest Spitsbergen than can be useful for dendrochronological research. It creates very narrow but clearly visible and well-defined growth rings. The constructed chronology covers the years 1951–2011 and is the first such development for this part of Spitsbergen. The extensive warming and changes in precipitation of the Svalbard archipelago during the last few decades correlates with the increase of growth rings width but in-tra-annual variability is also distinctly visible. The further increase of temperature and precipitation is projected by all climate models and therefore better understanding of climate-vegetation interaction is crucial.

– Consistent extreme pointer years (very narrow or wide ring widths) could be distinguished in many sections of constructed chronology. We found 13 extreme years in the Hornsund chronology, of which nine were negative: 1958, 1967, 1975, 1980, 1981, 1989, 1999, 2006 and 2010, and four were positive: 1963, 1966, 1976 and 1997. The occurrence of climate extremes for the Hornsund meteorological station is concurrent with the dendrochronological pointer years for the analysed polar willow.

– The presented results indicate the importance of deep snow cover for isolation, frost damage protection and also as a water reservoir during the growing season for Salix polaris. Negative years, the most important for dendroclimatological and ecological analyses, indicate unfavourable environmental conditions. The formation of narrow growth rings in the presented chronology is connected especially with the positive mean diurnal air temperature during winter and rapid thaw of snow cover, very low precipitation at the beginning of the growing season accompanied by a lack of snow cover in late spring and very low sunshine duration in summer.