. Introduction

Strike-slip and normal faults are the dominant sites of active tectonics in the interior of the Tibetan Plateau, and they control a series of basins and lakes characterized by extension since the late Cenozoic. In contrast, thrust faulting occurs along orogenic belts bordering the plateau (Molnar and Tapponnier, 1975, 1978, Tapponnier et al., 2001; Armijo et al., 1986, 1989; England and Houseman, 1989; Taylor and Yin, 2009). Northeast-trending left-lateral strike-slip faults north of the Bangong–Nujiang suture zone, and NW-trending right-lateral strike-slip faults south of the suture zone merge and intersect along the Bangong–Nujiang suture zone, forming a V-shaped conjugate strike-slip fault system (Fig. 1A) (Taylor et al., 2003; Yin and Taylor, 2011; Taylor et al., 2012). This system is kinematically linked to a N-trending rift system and is considered to accommodate convergence between India and Asia in the interior of the Tibetan Plateau (Armijo et al., 1986, 1989; England and Houseman, 1989; Taylor et al., 2003; Yin and Taylor, 2011; Ratschbacher et al., 2011; Styron et al., 2013, 2015; Sundell et al., 2013). Recent geodetic data show that the modern slip rates of right-lateral strike-slip faults are ~2–10 mm/yr (Wang et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004; Gan et al., 2007), perhaps lower for the Lamu Co Fault (0.1–8.0 mm/yr; Taylor and Peltzer, 2006), the Beng Co Fault (1–4 mm/yr; Garthwaite et al., 2013), and other strike-slip faults (Taylor and Peltzer, 2006; Garthwaite et al., 2013).

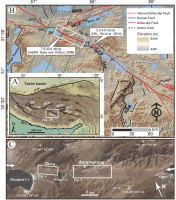

Fig. 1

(A) Sketch map of the tectonic setting of the interior of Tibet (after Taylor and Yin, 2009). (B) Map of the major active faults surrounding the Gyaring Co Fault (GCF) zone in central Tibet (white box marks the location in Fig. 1A) (after Taylor et al., 2003). The dotted green line indicates the InSAR sampling area for the GCF (Taylor and Peltzer, 2006). (C) GeoEye image for specified parts of the study area (white boxes). Abbreviations: ACF: Awong Co Fault; ATF: Altyn Tagh Fault; BF: Bue Co Fault; BCF: Beng Co Fault; DCF: Dongqiao Co Fault; GCF: Gyaring Co Fault; JF: Jiali Fault; KF: Karakoram Fault; LCF: Lamu Co Fault; MFT: Main Frontal Thrust; WCF: Wuru Co Fault; XGF: Xiaguo Fault; XDR: Xainza–Dinggye Rift; AKMS: Anyimaqen–Kunlun–Muztag suture zone; BNS: Bangong–Nujiang suture zone; JS: Jinsha suture zone; IYS: Indus Yalu suture zone; DGC: Dongguo Co; GMC: Gemang Co; ZNC: Zhangnai Co; ZGC: Zigui Co; GC: Gyaring Co (‘Co’ means ‘lake’ in Tibetan).

The average long-term slip rates of these right-lateral strike-slip faults, as determined from geological data, remain controversial due to insufficient chronological studies of well-preserved and faulted landforms. However, slip rates have been estimated in previous studies using a small number of absolute ages, or even speculative ages, and these studies have yielded rates with large uncertainties or contradictory results (Armijo et al., 1989; Ren et al., 2000; Taylor et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2010, 2012; Shi et al., 2014). The various slip rates have been interpreted in terms of two end-member models. Rapid geological slip rates (10–20 mm/yr) (Armijo et al., 1989) may indicate high-speed eastward crustal transport across Tibet, consistent with the rigid block model (Tapponnier et al., 1982, 2001; Avouac and Tapponnier, 1993). In contrast, relatively low geological slip rates (2– 10 mm/yr) (Ren et al., 2000; Shi et al., 2014) indicate distributed deformation across the V-shaped conjugate slip faults, consistent with a continuous deformation model (Molnar et al., 1993; England and Molnar, 1997; Yin and Taylor, 2011). Therefore, it is important to determine new and accurate long-term slip rates for these faults to better evaluate and improve our understanding of deformation models for the Tibetan Plateau.

The Gyaring Co Fault (GCF) is an active right-lateral strike-slip fault in central Tibet (Fig. 1), and forms the Karakorum–Jiali fault zone (KJFZ) along with the Karakorum Fault (KF), the Jiali Fault (JF), and other NW-trending right-lateral strike-slip faults. The KJFZ has been reported to represent the northern boundary of the rifts of southern Tibet, and the southern boundary of the eastward extrusion of the Tibetan Plateau that followed continental collision. Therefore, the GCF is an important active structure that is accommodating convergence between India and Asia in the interior of the Tibetan Plateau. The fault has displaced a series of well-preserved alluvial fans, lake shorelines, and rivers since the late Quaternary. Previous studies have reported abundant evidence of geomorphic offsets of these features (Armijo et al., 1989; Wu et al., 1992; He et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2010, 2011, 2012). However, slip rate studies of the GCF remain controversial due to the lack of robust ages that can directly constrain the chronologies of these faulted landforms (Armijo et al., 1989; Yang et al., 2010, 2011, 2012; Shi et al., 2014). Moreover, the discrepancy between the estimation of slip rates from geological (Armijo et al., 1989; Shi et al., 2014) and geodetic studies (Taylor and Peltzer, 2006) is difficult to resolve, given the sparse slip rate data for these faults in the interior of the plateau.

Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating is well suited to constraining the age of late Quaternary loess and sandy sediments (e.g., Lu et al., 2007). This method has been applied to the study of slip rates on faults in Tibet (e.g., Chen et al., 2013) and adjacent regions (e.g., Gong et al., 2015). In this study, we used OSL dating to constrain the late Quaternary slip rates from analyses of displaced landforms along the northern segment of the GCF at sites in Aerqingsang and Quba (Fig. 1C). We compare our results with previously published slip rates and discuss the long-term slip rate of the entire GCF. We then consider the discrepancy between the geological and geodetic slip rate data for the GCF, and implications for deformation in the interior of the Tibetan Plateau.

. Geological Setting

The GCF is a major active right-lateral strike-slip fault striking ~300° for a distance of ~240 km in central Tibet, south of the Bangong–Nujiang suture zone (Fig. 1A). From northwest to southeast the fault controls the locations of a series of lakes, such as Dongguo Co, Gemang Co, Zhangnai Co, Kong Co, Zigui Co, and Gyaring Co (‘Co’ means ‘lake’ in Tibetan) (Armijo et al., 1989; Taylor et al., 2003). These lakes may be expressions of negative flower structures (tectonic depressions or strike-slip grabens) (Sylvester, 1988) along the GCF due to extensional shear (Yang et al., 2011, 2012). The GCF merges with the N-trending Xainza–Dinggye rift near the southern shore of Gyaring Co and intersects the NE-striking Wuru Co Fault near the northern shore of Gemang Co (Fig. 1B), highlighting the regional kinematic connection between strike-slip and normal faults. Between these two intersection zones, the GCF shows most evidence for being active, and this constitutes a major segment of the GCF (Fig. 1B). Numerous late Quaternary alluvial fans, lake shorelines, and rivers have been displaced by between 3 and 500 m, indicating that the GCF has been active since the late Quaternary (Armijo et al., 1989; He et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2010, 2011, 2012).

. Methods

Geomorphic analysis

Fault mapping and geomorphic analysis along the northern segment of the GCF were carried out using various types of data, including field observations and topographic data (e.g., real-time kinematic measurements (RTK)) and satellite images (GeoEye images from Google Earth; resolution ~0.5 m). We mainly focused on the abandoned western edges of alluvial fans and preserved river terrace risers as our landform markers, and then used the projected extension of these markers on to the GCF to measure the offsets (Huang, 1993; van der Woerd, et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007, 2008; Gold et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012, 2013). Given that the horizontal uncertainties for RTK data and GeoEye images are <0.5 m, measurement errors on the displacements mainly arise from the determination of markers and construction of fitting lines (e.g., Cowgill, 2007; Zielke et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2013).

In previous studies, landforms having linear structures such as clear fringe-like terrace risers and fluvial channels have been preferred in calculating the displacement on strike-slip faults (e.g., Cowgill, 2007). In arid regions, alluvial fans can also be considered to have a predictable geometry and to be useful geomorphic markers (e.g., Brown et al., 2002; van der Woerd et al., 2006). The clearly visible contrasts in surface color and roughening of different fan surfaces enables their identification on satellite images, field observations and relief maps (Burbank and Anderson, 2011). Given that alluvial fans are fan- or cone-shaped deposits crossed and constructed by streams, fan cross-sections are convex-shaped. Fan flanks are often linear negative topographic features (e.g., seasonal rills). The fringes of alluvial fans generally connect to low-lying terrains (e.g., lakes or rivers). The deposits of the alluvial fans are typically poorly sorted, angular gravels, and may even have boulders scattered on their surfaces. The sediment characteristics of the fans commonly contrast with the materials outside of the fan area. Therefore, color differences, linear negative topographic features, and sediment characteristics on the fan surface enable the location of the edge of an alluvial fan to be identified in high-resolution satellite images overlain with high-resolution relief maps, and in the field.

OSL dating

Our sampling strategy was primarily designed based on two considerations. Firstly, we focused on sampling sand lenses, in the case that such lenses could not be found we sampled alluvial gravel layers with a high sand content. Secondly, to ensure that the OSL samples represent the ages of faulted landforms, we mainly sampled the uplifted side of the GCF and the abandoned western edges of alluvial fans and/or preserved river terrace risers. This approach reduces the possibility that later erosion may influence our results and interpretations.

OSL dating was used to study the northern segment of the GCF at the Aerqingsang and Quba sites (Fig. 1). Six samples were collected from the alluvial sediments. To avoid potential exposure to daylight whilst sampling, sediments for equivalent dose (De) determination were only taken from the middle part of each steel tube under subdued red light conditions, whereas sediments at both ends of the tube were used for radioisotopic content (U, Th and K) measurements.

Quartz grains were extracted following Lu et al. (2007) and Aitken (1998). Samples of ~100 g were first treated with 30% H2O2 and 30% HCl to remove organic matter and carbonates, respectively. The samples were then washed with distilled water until it became neutral.

The 4–11-μm-sized polyminerallic grains were separated by settling following Stokes’ law and were then soaked in 30% hexafluorosilicic acid (H2SiF6) for 3–5 days in an ultrasonic bath to extract fine-grained quartz. Purified quartz grains were transferred to a stainless steel disc (9.7 mm in diameter) for OSL measurements.

Dry sieving was used to separate the 90–125 µm fraction, which was further separated by heavy liquid fractionation (liquid density between 2.62 and 2.75 g/cm3) to obtain quartz grains. After drying, the quartz grains were treated with 40% HF for 45 min to remove the outer layer irradiated by alpha particles and any remaining feldspar-grain. The grains were scattered onto a stainless steel disc (9.7 mm in diameter) for experiments. The purity of the isolated quartz was checked by infrared (IR) stimulation. All the measurements were carried out using an automated Daybreak 2200 OSL reader equipped with infrared (880 ± 60 nm) and blue (470 ± 5 nm) LED units, and a 90Sr/90Y beta irradiation source. The quartz OSL signal was stimulated at 125°C with blue LEDs and detected with an EMI 9235QA photomultiplier tube coupled with two U-340 glass filters.

For De determinations, the sensitivity-corrected multiple aliquot regenerative-dose (MAR) protocol was used to determine fine-gained quartz OSL ages for two samples (KCSE-OSL-3 and OSL-111) (Lu et al., 2007), and the other samples were analyzed using the single-aliquot regenerative dose protocol (SAR) for OSL dating (Murray and Wintle, 2000). All OSL ages are listed in Table 1.

Table 1

OSL ages of displaced geomorphic markers along the Gyaring Co Fault in central Tibet.

| Site and landformsMaterial | Sample No. | Depth (m) | U (ppm) | Th (ppm) | K (%) | Water content (%) | Dose rate (Gy/ka) | Equivalent dose (Gy) | Age (ka) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Areqingsang Fan1-fine sand | KCSE-OSL-3* | 0.80 | 1.71 | 14.50 | 2.04 | 15 ± 5 | 4.09 ± 0.22 | 249.08 ± 11.19 | 60.87 ± 4.30 |

| KCSE-OSL-4 | 2.10 | 2.52 | 13.87 | 1.91 | 15 ± 5 | 3.40 ± 0.11 | 370.77 ± 22.82 | 109.15 ± 7.62 | |

| Qu ba site1 Fan3-medium-coarse sand with gravel | OSL-113 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 6.92 | 1.81 | 10 ± 5 | 2.93 ± 0.11 | 56.10 ± 4.70 | 19.15 ± 1 .77 |

| OSL-115 | 1.10 | 1.66 | 7.84 | 1.75 | 10 ± 5 | 2.89 ± 0.11 | 56.66 ± 5.76 | 19.58 ± 2.12 | |

| Quba site 2 Fan6 (T1)-fine sand with gravel Fan6 (T2)-silty sand | OSL-111* | 1.00 | 2.20 | 8.51 | 1.69 | 10 ± 5 | 3.54 ± 0.19 | 29.39 ± 1.80 | 8.29 ± 0.67 |

| OSL-99 | 0.30 | 1.41 | 8.81 | 1.88 | 10 ± 5 | 3.14 ± 0.12 | 174.40 ± 13.81 | 55.61 ± 4.88 | |

* * Alpha efficiency for 4-11μm quartz-grain was taken as 0.04±0.01 (Lu et al., 2007)

* * Alpha efficiency for 4-11μm quartz-grain was taken as 0.04±0.01 (Lu et al., 2007)

. Results

We conducted a detailed geomorphic survey along the northern segment of the GCF, based on remote sensing interpretation and fieldwork. According to the degree of incision into the fans, sedimentological characteristics, and OSL ages (Table 1), we divided the alluvial fans along the GCF into four old to young stages: early Late Pleistocene (Q3); late Q3; Holocene (Q4); modern. Early Q3 fans are composed of semi-cemented, sub-angular, medium- to fine-grained gravel deposits. Gullies cut through Q3 fans and form two to five terraces with a total incision of more than ~5 m (e.g., Fan1; Figs. 2 and 3D). Late Q3 fans are angular, coarse-grained gravels with boulders overlying older alluvial fans, and cut by ~2 m depth incisions and dry gullies (e.g., Fan3; Figs. 4 and 5). Holocene (Q4) fans generally consist of sub-angular, fine-grained gravel, and the depth of incision is often <2 m and these have developed one or two terraces. The modern fans are typically composed of mixed angular gravels that are unvegetated, and are active braided rivers or gullies. Along the northern segment of the GCF, the early and late Q3 fans are the most widely distributed, and thus these provide the ideal features to study the ages of the faulted landscape. Given this geomorphic survey and our field investigations, we conducted further detailed geomorphic and fault surveys at the Aerqingsang (Fig. 2) and Quba (Fig. 4) sites.

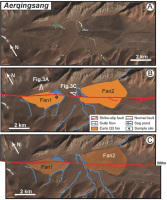

Fig. 2

(A) GeoEye image showing two early Q3 fans (Fan1 and Fan2) displaced at the Aerqingsang site. (B) Sketch map based on the Geo-Eye image. (C) Reconstruction of offset showing two fans consistently displaced by ~500 m.

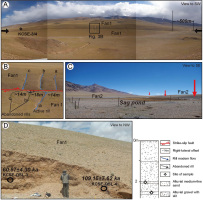

Fig. 3

(A) Mosaic photograph showing fault scarps, offsets, and sample locations on Fan1. (B) Close-up photograph showing fault scarps and three faulted rills on Fan1. (C) Photograph showing fault scarps and sag pond on Fan2. (D) Photograph and depth profile showing depositional setting and sample positions for Fan1 at the Aerqingsang site.

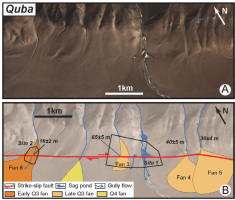

Fig. 4

(A) GeoEye image showing gully and displaced fans at the Quba site. (B) Sketch map based on the GeoEye image and field survey at the Quba site.

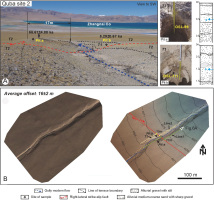

Fig. 5

(A) Reconstructed offset based on a 3D surface map (RTK) at Quba site 1. (B) Photograph showing faulted fluvial sediments that form a large sag pond. (C) Photographs and depth profile showing offset markers, depositional setting, and sample positions. (D) GeoEye image showing the displacement of Fan3 at Quba site 1. (E) Sketch map based on the GeoEye image and measurements of offset at Quba site 1.

Arerqingsang site

The Aerqingsang site is located south of Kong Co, near the village of Aerqingsang (Fig. 1C). At this site, the width of the Quaternary basin is only 2–4 km and strike-slip fault activity is mostly localized along a single strand. However, we located a series of secondary normal faults developed in the east of the basin, which form alinear depression with a length of ~3 km (Fig. 2). The major fault strand cuts across early Q3 and Holocene alluvial fans in their middle and fringe regions, forming linear fault scarps. Two early Q3 fans (Fan1 and Fan2) have been consistently right laterally displaced by hundreds of meters. To the east of Fan1 and west of Fan2, sag ponds occur along the northern side of the fault strand (Figs. 2 and 3). The primary sedimentary provenance of Fan1 is from the southern mountains, and aggradation has ceased (Figs. 2 and 3A). The linear scarps are very clear and are 2–5 m high. Several seasonal rills (30–400 m long) on the surface of Fan1 are displaced by ~3–40 m (Fig. 3A). Three rills are consistently offset by 14–18 m (Fig. 3B). Fan2 is still undergoing aggradation and has a sedimentary provenance from the northern piedmont, east of the Aerqingsang site (Figs. 2 and 3C). From east to west, the fault strand cuts the fringe of Fan2 and forms scarps with heights of 2–20 m. The landforms are better preserved on the southern uplifted side, and are locally eroded and reworked on the western fringes of these alluvial fans (Fig. 3C).

The surface color of Fan1 and Fan2 is dark brown and contrasts with the terrain beyond the fans (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the fringes of these two fans connect to streams. Thus, it is straightforward to identify the edges and areas of Fan1 and Fan2 (Fig. 2B). The right-lateral movement of the fault has displaced the fringes of these two fans, forming prominent shutter ridges on the southern side of the fault. The streams are dammed by the shutter ridges at the western fringes of Fan1 and Fan2 (Figs. 2A, 3A, and 3C). By retrofitting the western fringes of the alluvial fans and the dammed streams on both sides of the GCF using remote sensing images (GeoEye images from Google Earth), we identified a 500 m displacement for both Fan1 and Fan2 (Fig. 2). We estimate the error on this displacement to be 20%, and so obtain an offset of 500 ± 100 m (Fig. 2C), which is broadly consistent with previous interpretations (375 m by He et al., 2002; 400 m by Yang et al., 2012).

We located a ~3 m deep feature cut by a large gully on the southern uplifted side of the fault, in the eastern part of Fan1. Two OSL samples were selected from two sets of fine sandy lenses (20–40 cm thick). The results suggest that the upper and lower lens formed at 60.87 ± 4.30 and 109.15 ± 7.62 ka, respectively (Table 1). These ages may indicate Fan1 was deposited between ~61 and 109 ka (Fig. 3D). Fan1 and Fan2 consist of the same brown–red, sub-angular gravels in a matrix of silty sand (Fig. 3), and they have similar dark brown surfaces in GeoEye images (Fig. 2). Therefore, the two fans were probably deposited during the same period (i.e., early Q3 fans). Given the extensive age range of the fans, it is important to choose an appropriate initiation time for faulting in order to constrain the slip rate. This is a major factor in estimating the slip rate, and has been considered in many previous studies (e.g., van der Woerd et al., 2006; Cowgill, 2007; Zhang et al., 2007, 2008; Gold et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012, 2013; Gong et al., 2015). If right-lateral slip has occurred since the alluvial fan ceased aggrading, then the initiation time of faulting will be younger than ~61 ka and the average slip rate will be >8.2 ± 1.7 mm/yr. However, if right-lateral slip commencement coincided with the onset of alluvial fan aggradation, then the initiation time is ~109 ka and the average slip rate is 4.6 ± 1.0 mm/yr. We note that the aggradation capacity is limited at the fringes of the two fans where the fault strand crops out, implying that the western fringes of these two fans have been protected by uplift and right-lateral movement. Therefore, we consider that displacements has been occurring since the initial aggradation of Fan1 and Fan2. As such, the two early Q3 fans have been displaced by 500 ± 100 m since ~109 ka at an average slip rate of 4.6 ± 1.0 mm/yr.

Quba site

The Quba site is located south of Zhangnai Co where a major strand of the GCF strikes along the front of the northern mountains. The height difference of features at this site exceeds 1000 m. The piedmont is occupied mainly by early and late Q3 alluvial fans. A river of ~10 km in length originates in the northern mountains and flows southeast into the Kong Co. It cuts an early Q3 fan and has created two to three river terraces. The linear strand of the fault cuts across several alluvial fans and rills, and has dammed this river, forming a boot-shaped sag pond (Fig. 5B). Two late Q3 fans (Fan4 and Fan5) have been displaced at the apex (fan head) of the fans. Minor normal faulting and the relief have formed an uphill facing fault scarp with a height of 1–2 m. Long-term right-lateral movement has resulted in the western edges of the alluvial fans becoming abandoned (i.e., no longer receiving sediment from the fan head), revealing the history of fault displacement (Fig. 4A). The surface color of Fan3, Fan4, and Fan5 is brown, marked by small dark dots and short lines on the satellite images, which contrasts with terrain outside the fans (Fig. 4). The fringes of Fan4 and Fan5 connect to streams and a lake (Kong Co), and the flanks of these fans form dry rills (Figs. 4A and 5D). In the field, we discovered that the dark dots and lines are black angular gravels, or even boulders scattered on the fan surfaces. Moreover, beyond the fan region there are virtually no black angular boulders (e.g., Fig. 5C). Thus, we used these features to define the coverage areas of Fan3, Fan4, and Fan5 (Fig. 4B), and measured the displacements at their western margins using GeoEye images. The right-lateral offsets determined for Fan4 and Fan5 are 40 ± 5 and 36 ± 4 m, respectively (Fig. 4B).

At Quba site 1, Fan3 has one of the best-defined geomorphic markers comprising black angular tuff boulders on its western edge, which we studied in detail using a high-resolution satellite image (Figs. 5D and 5E). We used the method of projecting piercing lines onto the fault trace to measure fault offset (updated in Chen et al., 2013). The western flank of Fan3 is relatively linear and can be used to construct piercing lines. We then projected the piercing lines onto the fault trace from each side of the fault. The measured displacement between the two piercing points is ~65 m. A displacement of ~80 m was obtained from the eastern flank, but this result is not reliable due to the unclear nature of the fan margin (Figs. 5D and 5E). The black angular boulder deposits form a gravel ridge line (GR Line) on the western edge of Fan3 (Figs. 5C–5E). This GR line is also relatively linear, and thus is a good marker for offset measurement. We obtained a range of displacements from this feature of 60– 70 m, given that the upper part of the GR line has an uncertainty of ~10 m (Fig. 5E). Reconstructions of the offset from the three-dimensional surface topography show a best-fit displacement of 65 m. Using this value, the thalweg and eastern margin (or western margin of Fan3) of a dry rill have been reconstructed (Fig. 5A). We consider 65 ± 5 m to be a reasonable estimation for the displacement, with the relatively small uncertainty reflecting the young age and robust nature of the markers. We then collected two medium- to coarse-grained sand samples for OSL dating from the abandoned western edge of Fan3 on the uplifted side to the south of the fault (Fig. 5C). Although the difference between their sampling depths is >0.6 m, we obtained similar ages of 19.15 ± 1.77 and 19.58 ± 2.12 ka, respectively (Table 1). The similar ages indicate rapid deposition in this section and may suggest that the abandoned western edge of the fan has largely remained stable since 19 ka. This possibility is consistent with the absence of significant gully incision into Fan3 and the many black angular boulders on the surface of this fan area (Fig. 5C). Therefore, all the deposits of Fan3 may have formed during a very short time and remained stable since deposition. As such, the GCF has displaced Fan3 by 65 ± 5 m since 19 ka at an average slip rate of 3.4 ± 0.4 mm/yr.

At Quba site 2, a gully has incised into an early Q3 fan (Fan6) and forms a T2 terrace with a height (relative to the modern channel) of 3 ± 1 m and T1 terrace with a relative height of 1 ± 0.5 m. The T1 terrace was only deposited on the left bank, near the southern side of the fault (Fig. 6). Almost all the risers of the T2 terrace are adjacent to the modern channel. Thus, the risers of the T2 terrace are effectively gully banks. Right-lateral movement upon the fault has displaced the gully banks (risers of T2) (Fig. 6A). Given that deflected channels are usually subjected to water erosion when they change direction, stream deflections are not limited to the fault zone but extend beyond the fault (e.g., Huang, 1993). The upper parts of the gully banks are reasonably linear, so we used these to construct gully fitting lines and then piercing lines (Line1 for the east bank and Line2 for the west bank) from each side of the fault; the lines were projected onto the fault trace. This yielded displacements between the piercing points of 17 and 15 m, respectively (Figs. 6A and 6B). The studied gullies have reasonably linear channels, resulting in small uncertainties (Chen et al., 2013), and as a result a ~10% uncertainty was assigned, yielding an average offset of 16 ± 2 m for the gully bank.

Fig. 6

(A) Photographs showing gully offset and sample locations, along with a depth profile of the depositional setting at Quba site 2. (B). GeoEye image showing a displaced gully at Quba site 2, along with a geological interpretation and measurements of offset.

We collected two samples from the lower deposits of T1 and surface deposits of T2 on the southern side of the fault (Fig. 6). The T1 section (Pit b) consists mainly of loose, medium- to coarse-grained sand with gravel deposits comprising angular clasts, and a scour pit was found in the upper part of the section (Fig. 6A). At a depth of ~1.5 m the section reaches the height of the modern river bed. Below a depth of ~1.5 m the section comprises alluvial gravel and silt. The sediment characteristics are similar for the lower part of the section in T2 (Pit a) (Fig. 6A), which may suggest that both are deposits of Fan6. As such, dating of the surface deposits of T2 would constrain the maximum age of the gully, and dating of the lower deposits of T1 would constrain the minimum age of the gully. OSL results show that the maximum age of abandonment of the T2 terrace (gully banks) is 55.61 ± 4.88 ka (Table 1), whereas dating of the earliest deposits of the T1 terrace suggests that the minimum age of the T2 terrace (gully banks) is 8.29 ± 0.67 ka. We also interpret that the gully is relatively young, given the relatively shallow incision depth (~3 m) and small drainage area. The T2 terrace represents an abandoned original fan surface, and its age (~56 ka) is consistent with the age of the upper sand lens in Fan1 (~61 ka). Moreover, the displacement of this gully is also consistent with the rill offsets (14–18 m) on the surface of Fan1 (Fig. 3B). The age of the gully is not equivalent to the surface age. We also note that the T1 terrace was only deposited on the left bank and has since been protected by the right-lateral offset. Therefore, the onset of deposition of T1 is likely to document the displacement history of this young gully and yields a slip rate of 1.9 ± 0.3 mm/yr.

. Discussion

We have obtained three new slip rates at the Aerqingsang and Quba sites. These results yield slower slip rates along the GCF since the late Quaternary as compared with an earlier study (Armijo et al., 1989). Our results are similar to the late Holocene slip rate reported by Shi et al. (2014), which was constrained by OSL ages of faulted shorelines (4.1–4.4 ka) at the eastern edge of Zigui Co (2.2–4.5 mm/yr; Shi et al., 2014). Although our average Holocene slip rate (1.9 ± 0.3 mm/yr) is slightly lower than this, our upper limit is 2.2 mm/yr and is consistent with the result of Shi et al. (2014). Therefore, these results indicate that the average slip rates along the GCF (~2–6 mm/yr) have been <10 mm/yr since the late Quaternary. We have also investigated the slip rates over different geological time scales. In the early part of the late Quaternary (~109 ka), the average slip rate of 4.6 ± 1.0 mm/yr was relatively high. This rate has decreased to 3.4 ± 0.4 mm/yr since ~19 ka, and further decreased to 1.9 ± 0.3 mm/yr since ~8.3 ka. These three slip rates may indicate temporal variations in the longterm slip rate along the GCF throughout the late Quaternar y, although the uncertainties on the slip rates do not allow us to state this definitively.

In addition, discrepancies exist between the estimation of slip rates along the GCF from geological studies (2–5 mm/yr; Shi et al., 2014; this study) and geodetic studies (InSAR [1992–1998]; 7.5–20.8 mm/yr; Taylor and Peltzer, 2006) (Fig. 1B). Notably, other strike-slip faults such as the Lamu Co Fault (0.1–8.0 mm/yr; Taylor and Peltzer, 2006) and Beng Co Fault (1–4 mm/yr; Garthwaite et al., 2013) have relatively low short-term slip rates. Moreover, in the interior of Tibet, InSAR data have shown that the overall geodetic slip rate of the right-lateral strike-slip fault system is only ~6 mm/yr (Taylor and Peltzer, 2006). GPS data have also shown that the slip rate of the right-lateral strike-slip fault system is <10 mm/yr (Chen et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004; Gan et al., 2007), or an even lower rate of 2–3 mm/yr (Wang et al., 2002). Therefore, our lower long-term slip rates along the GCF are consistent with the overall slip rate determined for this right-lateral strike-slip fault system from geodetic data. These results suggest that long-term geological and geodetic slip rates are broadly consistent and that the discrepancy along the GCF is probably due to the limited number of geodetic observations.

Previous studies have reported that the right-lateral slip rates of the Jiali Fault, Beng Co Fault, and GCF are 10–20 mm/yr (Armijo et al., 1986, 1989). The ages of the faulted landforms used in those studies were not directly dated, but instead were derived from glacial–interglacial cycles. These faults are located east of the Karakorum Fault and together constitute the KJFZ (Fig. 1A). The KJFZ has been interpreted as the southern boundary of the eastward movement of the Tibetan Plateau, with relatively high slip rates of 10–20 mm/yr, accommodating at least 30% of India–Asia convergence with the Altyn fault and Kunlun fault (Armijo et al., 1986, 1989). Thus, these previous studies supported the rigid block deformation model (Tapponnier et al., 1982, 2001; Avouac and Tapponnier, 1993). However, other recent studies and our results suggest that both geological slip rates along the GCF (~2–5 mm/yr) (Shi et al., 2014; this study) and geodetic slip rates on other right-lateral strike-slip faults (Chen et al., 2004; Taylor and Peltzer, 2006; Garthwaite et al., 2013) are <10 mm/yr. These new data do not support the rigid block deformation model for the Tibetan Plateau, whereby deformation is localized along major strike-slip faults such as the KJFZ. In such a model, the slip rates of these right-lateral strike-slip faults should be relatively high (10–20 mm/yr), but this is inconsistent with our results. In addition, the overall geodetic slip rates of left-slip and right-slip faults are largely consistent (Taylor and Peltzer, 2006). For example, geodetically constrained left-slip rates of the Riganpei Co Fault (3.4– 11 mm/yr; Taylor and Peltzer, 2006) and Dongqiao Co Fault (1–2 mm/yr; Garthwaite et al., 2013) are also consistent with right-slip faults such as the Lamu Co and Beng Co faults. These data indicate that this V-shaped strike-slip fault system has had a relatively low slip rate since the late Quaternary. Hence, deformation may be distributed across the entire Tibetan Plateau (Taylor et al., 2003; Yin and Taylor, 2011) and the strike-slip system is kinematically linked to the N-trending rift system, which thus accommodates convergence between India and Asia in the interior Tibetan Plateau by slow outward extension (Molnar et al., 1993; Zhang et al., 2004).

. Conclusion

We have constrained the long-term slip rate of the GCF over three different time scales since the late Quaternary. Our results indicate that the GCF has accommodated displacement of 500 ± 100 m since alluvial fans were deposited at Aerqingsang from ~109 ka, suggesting an early Late Pleistocene (Q3) slip rate of 4.6 ± 1.0 mm/yr. The slip rate may then have decreased to 3.4 ± 0.4 mm/yr at ~19 ka, as inferred from a late Q3 fan (offset by 65 ± 5 m) at Quba site 1. The Holocene slip rate continued to decrease to 1.9 ± 0.3 mm/yr, as inferred from gully banks (offset by 17 ± 2 m) at Quba sit 2. Our estimated slip rates are lower than those from derived from InSAR (1992–1998) data (7.5–20.8 mm/yr; Taylor and Peltzer, 2006) but are generally consistent with late Holocene slip rates (2.2–4.5 mm/yr; Shi et al., 2014) and geodetic slip rates on other strike-slip faults (Taylor and Peltzer, 2006; Garthwaite et al., 2013). These data indicate that deformation is distributed across the entire Tibetan Plateau. Moreover, we speculate that the slip rate has decreased slightly along the GCF during the late Quaternary, although this cannot be stated definitively. To improve these uncertainties, further studies are needed to determine the geodetic and geological slip rates of strike-slip faults in central Tibet.